Category: History

-

Harry Weldon, music hall comedian

The comedian Harry Weldon is buried in Hampstead Cemetery, Fortune Green Road, in a grave close to other music hall performers: the famous Marie Lloyd, and the husband and wife act called ‘This and That’: James and Clarice Tate. Co-incidentally, it was said that that as a young man, Harry got the idea of going on the stage when he delivered a bouquet to Marie Lloyd.Harry was born James Henry Stanley in Liverpool on 1 February 1882. He worked as a clerk in a shipping office and next as a florist’s assistant while performing as an amateur. His first professional engagement was as a member of a touring group run by the wonderfully named ‘Professor Hairpins’. It wasn’t very successful and Harry often had no money: ‘It was sometimes necessary to leave the landlady at short notice and without paying. I used to write their names on the backs of bills and send on the money when I could.’Harry’s first stage appearance was at the Tivoli Music Hall, Barrow, in March 1900. He proved so popular that by November 1901, he was appearing at the Marylebone Music Hall in London. He developed his act using a prolonged whistle to accentuate the letter ‘S’, which became his much imitated trade mark: ‘Sno use’ became a classic expression. He was also known for his ‘clean’ jokes and routines. ‘Stiffy, the Goal-Keeper’; ‘The White Hope’ and ‘Bronzo, the Bull Fighter’ are among his best known sketches. Another character he developed was ‘Dick Turpentine’, a comedic take on the well known highwayman, you can see a cartoon of him at:In 1907 Harry was in Fred Karno’s company when he was first cast as ‘Stiffy’ in ‘The Football Match’ routine. Two different stories are told about this sketch, but both feature a young unknown by the name of Charlie Chaplin, then working for Karno on a meagre salary of 35 shillings a week. In the first version, Charlie is Harry’s understudy and he almost collapses from fright when he has to go on at a moment’s notice. Harry was supposed to have said of Chaplin, ‘he was so stiff he left ‘em cold, but he was one of the most unassuming and kindly fellows that one could meet.’ The other recalls Charlie playing the villain who tries to persuade Stiffy to ‘throw’ the match, offering him huge amounts of whisky which the goalie refers to as ‘training oil’. Whichever is correct, a recent biography of Chaplin claims Charlie was by far the better comedian and upstaged Harry, who far from praising him, never forgave him.After playing ‘Stiffy’ for many years, Harry presented ‘The White Hope’ – a boxing act. A stooge in the audience always responded to Harry’s challenge, ‘Come up and be knocked out!’ But one night the British champion boxer Billy Wells stepped onto the stage instead! The men became friends and when Wells was fighting Colin Bell (1914) Harry feigned a bad throat and lost voice to cancel a performance and go to the bout. When Wells knocked out Bell, Harry stood up and roared, ‘Hurrah, he’s out, he’s out!’ Elated, he turned round and saw Frank Allen sitting behind him. Allen was the managing director of New Cross Empire where Harry had been booked to appear that evening! Weldon soon added ‘Tell ‘em what I did to Colin Bell’ to his repertoire. In 1922, Harry appeared at the Royal Variety performance, an honour denied to Marie Lloyd, because of her risqué songs and troubled private life.Harry was married twice: for the first time on 29 August 1902, to Clarice Mabel Holt. Born in Manchester the daughter of the owner of a music shop, Clarice was a ‘vocalist’ who may have been a stage performer. Harry and Clarice had a daughter Mabel, known as Maisie, who was born in September 1906. But the marriage was an unhappy one. The couple formally separated in March 1922 and never lived together again. In 1925 Clarice divorced Harry on the grounds of his adultery with Hilda Glyder. They’d been living together at Alexandra Court, Maida Vale for some time. Hilda was an attractive but diminutive American, just 4 foot 11 inches tall and some 16 years younger than Clarice. Hilda came to Englandabout 1914 and made a career for herself as a popular singer and comedienne.Hilda and Harry appeared together in many productions including the 1923 and 1924 Christmas pantomime, ‘Dick Whittington’ at the London Palladium. He was one of the villains and she played Alice, who falls in love with Dick. They were married in June 1926.The adverts for their appearances show a relentless schedule of touring, appearing for a few nights at venues the length and breadth of the country. Harry appeared a couple of times at the Kilburn Empire in 1915 and 1916, while Hilda played the Empire and Willesden Hippodrome on several occasions during the early 1920s. In the days before radio and TV, a performer could use a song or a routine for many years before needing new material. There were always fresh audiences and fans were happy to revisit an old favourite. In Hilda’s case, however, some reviewers did politely suggest she would benefit from some new songs.Harry had been suffering health problems since 1923. At the end of a tour of South Africa in 1929, Hilda told the press that ‘she and Mr Weldon are feeling fine’ but in fact Harry was seriously ill. The couple landed at Southampton that September and Harry never recovered, dying at his London home, 132 Maida Vale, on the 10 March 1930. His graveside at Hampstead Cemetery was lined with spring flowers and a large number of fellow performers were among the mourners. At the funeral Hilda fainted and had to be helped to her car and taken home. Many stage performers sent floral tributes, among them one from Charles Gulliver, the owner of the Palladium: ‘In memory of one of England’s greatest comedians.’ Harry left his widow just over a £1,000.You can judge for yourself and see a recreation of the ‘Football Sketch’ on YouTube or hear Harry singing ‘I’m Going To See Old Virginie’. You can also buy a CD of Weldon at http://www.musichallcds.co.uk which lets you download a short extract of him singing ‘Stiffy the goalkeeper’.Hilda returned to the stage for some years. She remarried businessman David Gerry and died in New York in 1962. There are images of her on the web, painted by Walter Sickert and a 1913 photo, taken just before she came to try her luck in England.Harry’s daughter Maisie Weldon also went on the stage, as an impersonator and singer. In 1931 she married theatrical manager Fred Finch but he died two years later. Maisie continued to perform, ‘the famous daughter of a famous father’, and in 1950 she married Carl Carlisle, another impersonator. The couple became well-known radio ‘stars’ and there is a short 1941 British Pathe film clip of her singing and doing impersonations, including a very sibilant one of her father Harry. The problem for modern audiences is how to identify exactly who’s being impersonated! There’s also a British Pathe clip of her husband (1943) where he helpfully names the actors he’s impersonating. -

An artist and astronomer

While searching the catalogue of the British Museum for material about Kilburn, I found this delightful sketch of a farm. It was probably painted in the 1860s when there were several farms on both the Hampstead and Willesden sides of the Kilburn High Road and gives some idea of the rural nature of the village at the time. Unfortunately, there are no clues in the picture or any information about exactly where this was in Kilburn.

© Trustees of the British Museum The artist Nathaniel Everitt Green lived in Circus Road, St John’s Wood and would have walked to Kilburn, looking for inspiration in the countryside. Green was born in Bristol in 1823 and after starting in a merchant’s office in Liverpool found he did not like commercial work. So in 1844 he enrolled at the Royal Academy School where his contemporaries included John Everett Millais and Dante Gabriel Rossetti who founded the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. Green became a well-known artist and exhibited 18 landscape paintings at the Royal Academy between 1857 and 1885. He needed to earn a living for his large family of five daughters and four sons and became a successful teacher of painting and drawing to private pupils. In 1880 he was invited to Balmoral where his pupils included Queen Victoria, the Princess of Wales and other members of the Royal family. Green produced an instruction manual called ‘Hints on Sketching from Nature’ which was published by George Rowney and Company in 1871 and subsequent years. Rowney also produced the print of the Kilburn farm above.In 1859 Green became interested in astronomy and built his own telescope. He maintained his dual interests in art and astronomy and became a prominent member of the Royal Astronomical Society (RAS) and was the President of the British Astronomical Association (BAA) from 1896 to 1898. He set up a large reflecting telescope in his garden in St Johns Wood and used his artistic skills to make detailed pastel drawings of his observations of Mars. In 1877 he travelled to Maderia to carry out observations of the planet. Green became involved in the ‘great Martian canal debate’ and his findings were presented to the RAS and published two years later. He also made important contributions to the work about Jupiter.Green left London in 1899 and died in November at St Marks, Colney Heath, near St Albans. He was 76 years old.Further information:See the article by Richard McKim (BAA, 2004), Nathaniel Everett Green: artist and astronomer. Online:http://adsabs.harvard.edu/full/2004JBAA..114…13MSearch Google Images for “Nathaniel Everett Green” to see examples of his paintings. -

Engels and the bridge builder

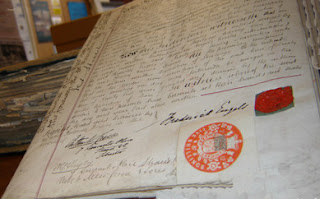

In November 2011 Kate Jarman, an archivist at Brent Archives, was going through some old mortgage documents when the name on one of them caught her eye. The property was a new house in Willesden Lane built by Samuel Blasby and Henry Hodges, who also built other houses in the Brondesbury area. The date on the mortgage was 25 March 1883 and the signature was that of Friedrich Engels, the joint author with Karl Marx of the Communist Manifesto (1848). This was previously unknown information about Engels.

Mortgage with signature of Friedrich Engels at Brent Archive Engels lived at 122 Regent’s Park Road Primrose Hill, from 1870 until his death in 1895. He had left his job as a mill owner in Manchester and moved to London to be near Marx, whom he saw every day at his house in nearby Maitland Villas. Engels obviously bought the Kilburn property as an investment: in June 1886 it was rented to Alfred and Fanny Emma Thorne and they bought it from him on 1 December 1887. Thorne and his family continued to live there until 1912.

Friedrich Engels The house was originally called ‘Kings Legh’ in various documents, although it sometimes appears with the spelling King’s Leigh. It was about half way along Willesden Lane, near the corner with Coverdale Road. When the area was re-numbered about 1886 it became 191 Willesden Lane. From the time of his marriage in 1875 until 1886, Alfred Thorne had lived on the Hampstead side of Kilburn at 25 St George’s Road, now named Priory Terrace which runs from Belsize Road to Abbey Road. He was born in Scotland in 1847 and became a civil engineer. Alfred Thorne and Sons of 7 Cartert Street, Westminster, specialised in bridge building. Newport Transporter BridgeIn 1906 they built the Newport transporter bridge. In 1908 they constructed the 292 feet long swing bridge at Littlehampton to replace the old ferry over the river Arun. The bridge linked Littlehampton to the towns of Portsmouth, Worthing, Bognor and Chichester.

Newport Transporter BridgeIn 1906 they built the Newport transporter bridge. In 1908 they constructed the 292 feet long swing bridge at Littlehampton to replace the old ferry over the river Arun. The bridge linked Littlehampton to the towns of Portsmouth, Worthing, Bognor and Chichester.

Littlehampton Swing Bridge

They also built the footbridge bridge to the Mizen Head fog-signal station in County Cork Ireland, in 1909 at a cost of £1,272. In 1911 the company built the Warrington bridge. Previously Thorne and Sons had constructed Pembroke pier in 1899.

Mizen Head Bridge, at the southern most point of Ireland

Alfred Thorne died at ‘Woolhara’ Haddenham, Bucks on 7 June 1923. He left £1,493 to his sons, Alfred John Parker Thorne and Douglas Stuart Thorne, who were both engineers in his company. His widow Fanny Emma Thorne died at ‘Woolhara’ in 1938.From 1980 to 2004 the house at 191 Willesden Lane was called ‘Homelea’ and was a Brent hostel for 11 mentally handicapped adults. In 2008 Brent Council approved demolition and it was rebuilt in a PFI scheme by Bouygues UK. They completed the seven flats in 2011 for Brent social housing. -

South Pacific tribal pieces in Kilburn

In 1895 a Kilburn man gave his collection of New Hebrides (now called Vanuatu) artefacts to Sir A.W. Franks, the keeper of Antiquities at the British Museum, and asked him to put them on display. This struck us as rather strange, what were the pieces doing in Kilburn and who was this man? -

Camden Town and Kentish Town: Then and Now

Our new book shows a series of old photos of Camden Town and Kentish Town, see together with what is there now.

We will be doing an illustrated talk at the Owl Bookshop on 12 July.

Camden Town in north-west London has become one of the capital’s most popular tourist destinations, attracting millions of people every year. They come for the markets, the food or special events such as the annual ‘Camden Crawl’ music festival.Camden Town and neighbouring Kentish Town developed along two major routes that led to the villages of Hampstead and Highgate. A cluster of houses near the present junction of Royal College Street and Kentish Town Road grew into the village of Kentish Town. The district of ‘Camden Town’ didn’t exist until 1791, when Lord Camden obtained an Act of Parliament to develop his fields east of Camden High Street. Other landowners soon followed his example and started building.As the nineteenth century progressed, a network of residential streets was created, lined with terrace houses or semi detached villas. The main roads became prime shopping areas, supplying most of the needs of local householders, along with churches, music halls and cinemas. The Regent’s Canal opened in 1820 and the London and Birmingham Railway began running trains through Camden Town to their terminus at Euston in 1837. Two more railway companies laid tracks across the fields of Kentish Town in the 1850s and 1860s. On the roads, horse buses were joined by trams and later replaced by motor and trolley buses. Industry was drawn to the streets near the railway lines and canal, providing much local employment, as did the railways themselves. The area became a noted centre of the piano making industry.In the years immediately preceding WWII Camden and Kentish Towns suffered a general decline. The area was polluted by soot and smoke from the trains. Many family-owned houses had been converted into flats or bed-sits and become run down. St Pancras, and later Camden Council, embarked on redevelopment schemes that eradicated entire neighbourhoods, replacing old properties with new accommodation, largely in the form of blocks of flats. Comparing the old and new images shows how many streets with their own local shops and facilities have disappeared.Today both Camden Town and Kentish Town are busy cosmopolitan neighbourhoods. Good road, rail and tube links have helped promote their popularity as residential districts. Many of the pubs continue to flourish, and some have become famous as live music venues. The late Amy Winehouse, who lived locally, was a frequent visitor and performer. Disused buildings and sites along the canal and railway lines have been adapted for housing and commercial use, notably the area in and around Camden Lock. The stalls and shops offer a huge variety of merchandise but the famous pet shop that for many years sold talking parrots and monkeys, has become a café. -

Wartime murder at Kilburn station

Kilburn Station, 2012 At 12.30 am on 12 December 1942in Kilburn and Brondesbury Metropolitan Station, Josephine Chapman was cashing up after the last train had gone. She heard a knock on the door and a voice saying, ‘Can I have a word with you? When she opened the door two men ordered her to hand over the money, but her screams were heard by station foreman George Gardiner who was fire watching. As he went to her help one of the men shot him three times and they ran down the stairs and into the darkness. Josephine, who had only recently started work at the station, was able to give a description of the two men to the police. She said that the man who fired the gun was young, aged about 18 to 20, about five feet seven inches tall, with an injury to his face and he was wearing a brown suit. The other man was slightly older wearing an overcoat. Both the men had felt hats with the brims pulled down.Forty six year old Gardiner was shot through the head, mouth and chest, and he died shortly afterwards. When the police arrived they found three cartridge cases from a .45 service revolver on the platform and a London-wide man hunt was started. The case was led by Superintendent L. Rundle from Scotland Yard, a very experienced man who had been head of the detective training school at Hendon, and Detective Inspector R. Deighton. The police stayed at the station until dawn and early morning passengers were unable to use one side of the pay box which was roped off. Detectives took away the door of the pay box to look for fingerprints and searched neighbouring gardens looking for the revolver, but found nothing.

Site of Pay Box Today George Gardiner, known as ‘Jock’ to his friends, had grown up and lived locally. He was born on 31 March 1896 at 6 Palmerston Road, where his father was a bricklayer. George had started work as a grocer’s porter. He was a quiet, reserved man and had worked at the station, today just called Kilburn Station, for several years. He lived at 15 Kenilworth Road, off Willesden Lane, and left a widow Alice Maud Gardiner and a son. He was buried at Willesden New Cemetery on 17 December (Section A, grave number 2510). Alice continued to live at the house until her death in 1965.Coincidentally, an hour before the murder, a man was shot during an argument at ‘The Lido’ dance hall at the other end of the Kilburn High Road; however, the police believed the incidents were unconnected. In the previous week there had been seven armed robberies in London. But these had been carried out by two men wearing army uniforms. Despite the large man hunt, nobody was ever arrested for Gardiner’s murder which still remains unsolved. -

West Hampstead at war

As London commemorates the 70th anniversary of the Blitz, I thought I’d take a look at how West Hampstead fared during the war. There are tales of amazing rescues, tragic stories of wedding parties, and some explanation for the streetscape we all inhabit today.

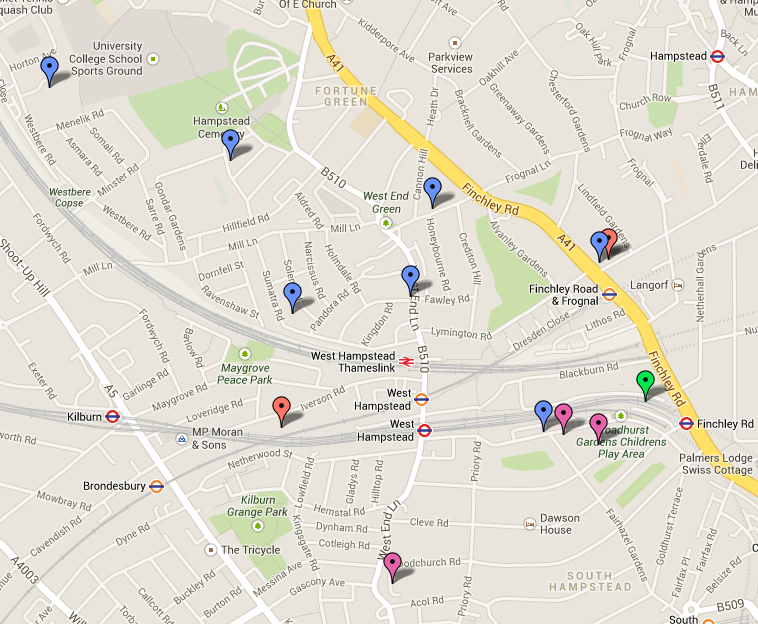

The old borough of Hampstead was not as affected as badly as some parts of London as it had no major military targets. Nevertheless, more than 200 people died in the borough as a result of bombing. The density of the railway lines around here probably contributed to some of the munitions that fell in NW6, a tiny number of which are mapped below.

View West Hampstead WW2 sites (a small selection) in a larger mapWest Hampstead itself escaped widespread damage, and large-scale rebuilding was not needed. Indeed, much of the 19th and early 20th century character of the area remained intact. But that is not to say that life was easy for residents during the two main periods of bombing raids: 1940/41 and 1944/45.

The first bomb to fall in the area hit Birchington Road at the end of August 1940, but the first serious damage in West Hampstead happened a couple of weeks later. The sirens sounded at 10pm on September 18th, and in the early hours of the 19th seven bombs fell between Mill Lane and Sumatra Road killing 19 people. In a macabre conicidence, 19 was also the number of houses destroyed. These included 76–86 Sumatra Road and 9–17 Solent Road.

It was a sharp wake-up call for wartime whampers many of whom – like people across the country – were only starting to believe that the war was ever going to be a direct threat to them.

A week later, another seven bombs struck in Broadhurst Gardens – the first strike of many for this road. Amazingly just three people died but only a few houses escaped damage. Ten days later, on October 7th, the central library on Finchley Road – now the site of the Camden Arts Centre – was badly damaged and a female warden on duty at the observation post was killed. This was a night of heavy bombing across the country. A wing of Hampstead School in Westbere Road (then Haberdashers School) was damaged; this plaque marks the event.

(photo courtesy of Ed Fordham)The Blitz lasted until May 1941, killing some 20,000 Londoners. Tube stations provided natural bomb shelters and Hampstead and Belsize Park were especially popular due to their depth. War artist and famous sculptor Henry Moore made some evocative sketches of people huddled together in Belsize Park tube. Residents had to get to these stations fast though as space was limited.

Swiss Cottage also served as a shelter, although initially there were no toilets and people had to take the train to Finchley Road to use facilities there. Councils began to realise that people were going to use the stations regardless so began to make them more comfortable, installing bunk beds, toilets and providing some refreshments.

Quite a community built up among the regular occupants of Swiss Cottage and they produced their own magazine called (honestly) The Swiss Cottager. There was a lobbying component to this publication. Bulletin No.2 claimed that “the installation of three-tier bunks on tube platforms would be hailed with relief by the thousands of people who nightly use the tube-station platforms as dormitories.”

The group also politely requested that shelterers refrained from bringing their own deck-chairs and suggested people were being “far too generous” with their litter.

Such doughty spirit was part of the reason Hitler turned his attention to other fronts and large-scale bombing of Britain subsided. He had failed to crush either the morale of Britons or sufficient industrial sites. Even during this lull in bombardment there was the occasional mishap: in 1943, a barrage balloon caught fire and fell onto houses on Gascony Avenue.

On Saturday February 19th, 1944 bombing began again. A bomb at the corner of West End Lane and Dennington Park Road struck a wedding party. The Camden History Society’s excellent Hampstead at War gives a full description of the explosion, which killed 10 people including two babies.

“In a flat over a butcher’s shop, a party was in progress attended by relatives and friends of the occupier’s son, a soldier who was to be married later that day. The company remained during the alert in unprotected rooms, no doubt lulled into a false sense of security by the long period of aerial inactivity. A high explosive bomb fell at ten past one in the morning demolishing the upper part of the premises over the shop… The premises were soon burning furiously and the rescuers were forced back time and time again.., The only survivor from the party was the father of the bridegroom who had left the room and gone to the rear of the house just before the bomb fell.”

The site wasn’t rebuilt until 1954, and today houses West Hampstead’s library.

That same night, eight bombs fell within 100 yards of each other at Agamemnon Road and, although only three exploded, 16 people were killed at what is now a terrace of three-storey houses built in 1952.

A few months later aerial bombardment intensified again when the V1 flying bombs entered service. Hampstead borough took 10 hits from V1s. Hampstead Town Hall was a vital observation point to track the V1s, and wardens would follow the bombs right to the point of impact – even if that was just yards from where they sat.

The first flying bomb hit a West End Lane house used as a hostel for refugees. Three houses were completely destroyed but the damage extended across five roads. Rescue efforts lasted two days and although 17 people died, a woman was found alive 48 hours after the bomb exploded.

The site was used to build Sydney Boyd Court in 1953, the large council estate that hugs the curve of West End Lane between Acol Road and Woodchurch Road.

In late June 1944, Broadhurst Gardens was struck again, at almost exactly the same point as in 1940. The following day, a building in Mortimer Crescent was hit – it was used to store furniture for people whose own houses had been destroyed. This was probably the same attack that forced author George Orwell out of his Mortimer Crescent home, where he had written Animal Farm. Further doodlebugs hit Fortune Green Road, Mill Lane (damaging an ambulance station) and Parsifal Road where a District Warden headquarters was damaged.

Broadhurst Gardens suffered yet more damage in August 1944 when a V1 fell in the gardens between Broadhurst and Compayne Gardens just 50 yards from the previous bomb. The road was the worst affected in the borough, which is why large stretches of it are occupied today with council housing.

More than 1,300 V2s fell on London (only Antwerp was targeted more) killing 2,750 people. Britain never developed effective countermeasures for these supersonic missiles. Of those 1,300 V2s only four had an impact in this area, with one causing particularly widespread damage.

Superlocal blog Northwest 6 covered wartime memories a couple of years ago. One reader, John Lewis, recalled “I was staying with my grandparents at 25 Gladys Road towards the end of WW2 when a V2 came down about 250m away in Iverson Road. I was covered in soot, dust and broken glass but unharmed.”

In 2004, the Camden New Journal printed an anecdote from Gladys Cox, who also recounted a bomb in Iverson Road. Although her account said it was in January 1944 it seems likely it was in fact the 1945 attack.

“After lunch, it stopped snowing, and as the air was invigorating we walked, or slithered in the slush, down to Iverson Road. Here, rows and rows of small houses had been blasted from back to front; doors, windows, ceilings all one. Whole families were out in the street standing beside the remains of their possessions, piled on the pavements waiting for the removal vans; heaps of rubble everywhere, pathetically showing bits of holly and Christmas decorations.”

The bomb actually fell on the railway embankment, but both sides of the railways suffered. The driver of the first rescue vehicle on the scene found one of the dead – his own 19-year-old daughter. One woman was rescued eight hours later after the rescue teams had almost given up. She was found jammed under a sink in the scullery.

Iverson Road was by far the worst affected street, but damage extended to Sheriff, Maygrove, Ariel, Loveridge and Lowfield Roads, Netherwood Street and West End Lane. Although only three people lost their life, 1,600 people required some form of assistance and 400 had to be temporarily rehoused. There’s another personal account of the attack at Northwest 6.

Seventy years later, it can all feel rather like a numbers game. So many people died, so many houses were damaged. It is impossible for most of us who have grown up in a peaceful western Europe to wrap our heads around the permanent sense of fear that must have underpinned lives for millions and millions of people across Europe during the war. The work of the civil defence organisations and rescue services should not be overlooked. They may not have received the plaudits of the fly boys in the Battle of Britain, or Monty’s Desert Rats, but their commitment to the lives of ordinary Londoners was astonishing.

Sources:

Hampstead at War, Hampstead 1939-1945, pub Camden History Society, 1995 (first published in 1946)

Wartime Camden, Life in Camden during the First and Second World Wars, compiled by Hart, V. & Marhsall, L, pub. London Borough of Camden, 1983

‘Hampstead: West End’, A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 9: Hampstead, Paddington (1989), pp. 42-47. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=22636