Luxury retirement development ‘can’t afford’ to pay for affordable housing

West Hampstead is facing yet another large-scale property development. It’s the third proposal to redevelop the site at the former Gondar Gardens reservoir. The history of the previous proposals have been well documented on these pages, but what really caught our eye about this one was that it offers no affordable housing either on-site or as a payment for development elsewhere. Previous schemes have offered about 35% affordable housing. The developers claim that as a care-home they are not legally obliged – but even if they were, according to their sums they couldn’t afford it!

A quick recap

There have been three planning applications for this site over the past eight years. Gondar Gardens is designated a site of importance for nature conservation (it has Camden’s only population of slow worms). Developer Linden Homes’ first scheme proposed 16 houses built low in the cavity of the old reservoir (the ‘pit’ or ‘Teletubbies’ scheme) with an off-site affordable housing contribution of £6.8 million. The second proposal was to build along the frontage of Gondar Gardens (the ‘frontage’ scheme’), which was turned down as the design wasn’t good enough. A revised frontage scheme was submitted for 28 flats, or which 10 were affordable plus a small additional off-site contribution. This scheme was approved on appeal and thus we all expected that Linden Homes would build this scheme and that would be that.

There’s a new developer on the scene

Instead, Linden Homes sold the site to a new developer, LifeCare Residences (LCR). LCR, which started in New Zealand, builds what it terms “exceptional retirement communities”. Here in the UK, it has one in Hampshire and another in Battersea. In West Hampstead, it’s proposing to build Persephone Gardens. Classicists will know that Persephone is the Queen of the Underworld. Odd choice of reference for a retirement village.

For Gondar Gardens, LCR proposes 82 self-care retirement apartments with a total residential floor space of 7,662m2. The flats include 7 one-bedroom, 62 two-bedroom and 13 three-bedroom flats. The total floor space of the whole development is 14,088m2 – almost double the floor space of the previous two schemes combined. Both of the previous schemes included about 35% affordable housing, although Camden’s (rarely achieved) target is 50%.

If this new scheme followed its predecessors, one would expect at least 30-40 affordable flats. But the plans show that none at all are proposed – nor is there any off-site contribution.

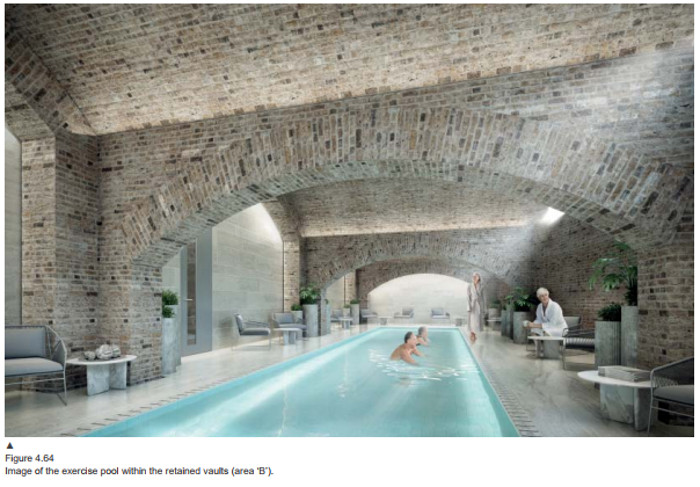

LCR is, however, building extra facilities for the residents on site because it is a retirement home, including a 15-bed nursing home. But it also plans ‘communal’ facilities – and what facilities: a lounge, a library, a restaurant and bar, and a café, an indoor exercise and rehabilitation pool, a gym. Wow! That’s a lot, you’re thinking. There is more: a hair salon, treatment rooms (of course), the sun lounge and, oh yes, a cinema. And of course a whole host of back-of-house areas for the staff.

The chauffeur-driven cars on site have already raised a few eyebrows. The development will be car-free, so LCR is planning to have chauffer-driven BMW i3s, like at its Battersea site, at the beck and call of residents, and for those who want to be ferried around in more comfort, a couple of Audi A8s too.

Are you beginning to notice something all the residents have in common?

If this all sounds rather luxurious, that it is the intention. Comparing the flat sizes to Mayor of London’s recommended size for new developments, LCR’s are generously proportioned. The flats are substantially bigger than the recommended size for flats in the London plan; e.g. the one-beds are 69m2 vs a recommended 50m2; the two-bed and three bedroom flats similarly generous.

The architects Robin Partington stated in the Design and Access statement: LCR’s brief requires the apartments to be larger than national space standards. Residents are typically downsizing from big family homes, and although there are only 1-2 people living in each apartment, space is appreciated to maintain their way of life and house their belongings“.

Finally, a non-white face in the promo images – he’s a waiter!

The luxury nature of the development is reflected also in the viability statement: “In the assessment of market values, which have been provided by Savills we understand that the specification of the common parts and apartments will be of a very high quality and reflective of the luxury retirement living that the scheme will deliver.”

Why no affordable housing?

The first argument is a bit technical and has to do with use classes. LCR states that the flats should be designated as class C2 (hospital or nursing home) rather than C3 (housing). It’s understandable that the 15-bed nursing home would be C2, but the 82 flats? One common way to determine if a property is C2 or C3, is the ‘front door test’. If residents have their own lockable front door, then the flats should be C3, and it seems that would be the case here in these generous flats. To get around this definition, LCR will offer a couple of hours of assistance per week, whether the residents want it or not.

This approach has been tried before. Another retirement home developer, Pegasus Life, tried the same idea for the equally luxurious Hampstead Green Place on Rowland Hill in Hampstead. It argued the housing was C2 (offering 1.5 hours of care a week) but lost the argument and the 60 flats are being built as C3.

The other argument used by LCR is the standard plea of poverty – or at least too low a profit margin.

Linden Homes bought the site from Thames Water for £3 million, and those proposals allowed for £6.8 million to affordable housing in the first scheme and 10 affordable flats in the second. Linden Homes sold the site to LCR for £11 million according to the Land Registry records.

What does the viability statement say?

*Warning it’s going to get a bit complicated here, but bear with us, it’s important*

LCR commissioned property consultancy Rapleys to write a viability report to submit with the planning application. It’s hard to follow as it’s redacted, but it is possible to make some educated guesses as to what the numbers might add up to on a development of this scale, with the help of industry insiders.

To reach its conclusion, Rapleys had to calculate the “residual land value”, which is Gross Development Value (basically “revenue from the sale of flats”) minus costs, planning contributions, and profit (typically assessed at around 20%). This is then compared to an appropriate benchmark value to assess the viability of affordable housing contributions.

Let’s do the sums.

First, the gross development value. To calculate this, we need to know how much private flats like these would be worth? We have a good benchmark with the high-end West Hampstead Square development, which also has some amenities (though nothing in the league of the proposal from LCR). Gondar Gardens is further from the stations, which makes it cheaper, but also not between two train lines. On balance it’s easy to argue Gondar Gardens would sell for more than West Hampstead Square, but WH Square will be a good benchmark. On this basis (looking at recent resales), a 69m2 one-bed flat in Gondar Gardens would be £825,000, a two-bed 90m2 flat £995,000, and a three-bed flat a cool £1.35 million.

(Interestingly, in nearby Hampstead, Pegasus Life is marketing two posh retirement schemes although with fewer amenities. Nevertheless, at one of these schemes, the cheapest two-bed flat is on for £2.95 million, so we may we wildly underestimating Gondar Gardens).

Sticking with the Ballymore equivalents, the sale of the flats would generate approximately £85 million. The fifteen extra care beds have a market value, like all care-home beds, of about £295,000 each, so are valued at £4.5 million. Adding the two together gives a total gross development value of £89 million.

Now we need to look at the costs of development. Rapleys don’t disclose the construction costs but based on this nearby scheme (which is equally modern, but a bit less posh), we estimate construction costs for a development like LCR’s would be about £2,500/m2 for the 14,088m2. This is perhaps the number with the most margin for error in our calculations given that just under half of the development is taken up with all those facilities. However, LCR is effectively arguing that building all these extra luxury facilities means it won’t have any money to build affordable housing. By comparison, a normal housing development would have 10-15% of ancillary space (corridors, communal areas etc).

In total, we estimate build costs of around £35 million. Add to that a 5% contingency (£1.75 million), professional fees at 10% of costs (£3.5 million) and marketing fees – 2% of GDV to sell the flats (£1.6 million).

Then there are community infrastructure levy (CIL) costs (this is the money that developers pay local councils and City Hall to help offset the additional public sector costs incurred by having more people and development in the area). Normally CIL is calculated on the increase in residential floor space, as this is the driver of any additional strain on local resources. For Gondar Gardens, LCR is arguing that the increase in area is 9,242m2, not 14,088m2, using the empty and derelict reservoir space of 4,866m2 as the “existing use”. There is a clear change of use, so it’s not clear why LCR does not using the full 14,088m2 to calculate their contribution.

Under its proposal, Camden would receive a CIL contribution of £2,310,500 and City Hall would take £462,100 (if the full development area was used, there would be an additional £2 million of combined CIL due).

Revenue minus costs, therefore, is calculated as £89 million less build costs of £35 million, a contingency of £1.75 million, marketing fees of £1.6 million, professional fees of £3.5 million and a total CIL of £2.75 million. That gives a gross profit of £44.m million. The accepted 20% profit margin of the GDV is £17.7 million, which leaves a residual land value of £26.7 million. The numbers are obviously not exact but our industry insiders agree this is a good ballpark figure.

This residual land value basically translates to “extra profit”, which means that it’s where contributions to affordable housing would come from. Recall, that based on a much smaller scheme, Linden Homes was offering a contribution of more than £6 million. If LCR was to make a contribution then using the calculations from the Pegasus schemes in Hampstead (for which Rapleys also produced the viability report) it would deliver a £10.6 million contribution.

Yet below is their redacted claim that they can’t afford any affordable housing contribution.

Our estimate of the residual land value of £26.7 million is considerably more than the £11 million LCR paid for the site. Even if we deduct an affordable housing contribution of £10 million (which, LCR claims it can’t afford), that would still leave a residual value of £16.7 million – still more than the cost of buying the site. Even if our building costs are wrong, they would have to be substantial underestimations to soak up all this residual value. It is therefore hard to understand how no affordable housing contribution at all is deemed viable. Perhaps the expected sale value of the flats is far lower than comparable schemes.

LCR/Rapleys instructed Carter Jonas to carry out an independent valuation of the site to form the benchmark value. They don’t disclose this, but obviously it would be interesting to know how it compares to the £11 million that LCR paid for the site (bear in mind also, that the site comes with planning permission for the revised frontage scheme and its £6.8 million affordable housing contribution).

LCR told us that that have commissioned a further independent assessment of the assessment and were in discussion with Camden’s appointed surveyor, but had no further comment.

Conclusion

This proposal illustrates a significant flaw in the planning system that gives an advantage to developers of luxury retirement schemes. First, such developers are incentivised to claim such schemes are care home and not housing, even if they pass the front door test. Then, the more luxurious they make it and the more ancillary facilities they offer (and have to pay for), the more they can avoid making any affordable housing contribution.

This analysis has also been an interesting insight into the Alice-in-Wonderland economics of viability reporting. It’s important stuff, but too often developers deploy smoke and mirrors around the planning department and unless at least some members of the public understand what is going on developers get away with it. Why, for example, should so many of the figures be redacted? We had the same situation with Liddell Road, which was publicly owned land and being used partly for a public amenity.

Part of this is due to the merry-go-round of a developer buying a site and getting planning permission for one scheme and then selling it on to another, ratching up the base value. One reason for the planning system is to capture some of the financial gain when land is redesignated for another use. Yet it appears developers can drive a chauffer-drive BMWi3 though that objective.

Baby boomers lucky enough to have bought their houses in the 1970s and 80s and have made huge windfall gains. They now get sell them and move into luxury retirement flats that avoid the requirement to build affordable housing. A competing developer that was building ordinary flats for young people and young hard-working families would have to build affordable housing. Sorry, Generation Rent, it’s heads you lose, tails they win.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!