“They had no choice”: Kilburn’s Animal War Memorial Dispensary

The recent commemoration of the centenary of the outbreak of the First World War has focused many people’s thoughts on the service men and women who fought, died and survived the conflict. Ten years ago, attention centered on the millions of animals and birds that served alongside British, Commonwealth and Allied troops in all conflicts during the twentieth century. The memorial to Animals in War in Park Lane was unveiled on 24 November 2004. An inscription reads, ‘They had no choice.’ But Kilburn is home to a much earlier – and more active – memorial to the nation’s service animals.

Horses, dogs and donkeys were the most commonly used animals – mainly for transport and haulage, but camels, elephants, pigeons, bullocks, dogs and goats were all pressed into service. They suffered from exposure, lack of food and disease, dying alongside their human companions.

The Park Lane memorial was the fulfilment of an idea that dates as far back as the early 1920s when the RSPCA proposed a memorial for animals that had served in WWI. A committee was set up, funds were raised and the site chosen was Hyde Park corner. In 1925 photographs of the proposed memorial were submitted to Westminster City Council but there the project appears to have stalled.

Instead the RSPCA decided on a more practical commemoration, in the form of the Animal War Memorial Dispensary in Kilburn, where, in the words of a contemporary report, ‘the sick, injured or unwanted animals of poor people could receive, free of charge, the best possible veterinary attention, or a painless death.’

It took many years to find a site for the Animal War Memorial Dispensary. The RSPCA acquired 10 Cambridge Avenue in March 1931 and that May, the freeholders allowed a change of use from a private house to a ‘free dispensary for sick and injured animals.’

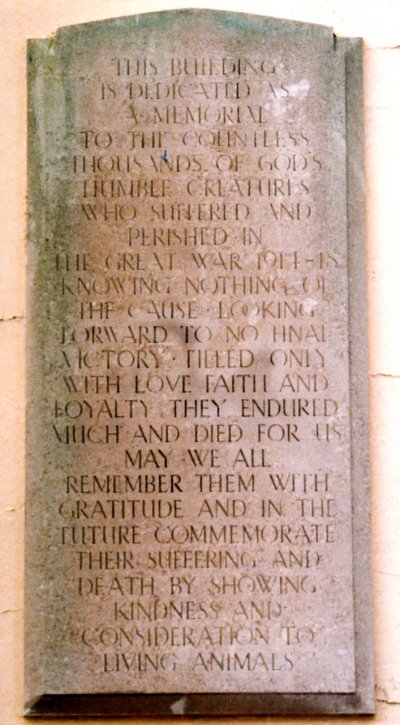

The memorial inscription on the Kilburn building is echoed by that in Hyde Park: ‘To all animals who suffered and perished in the Great War knowing nothing of the cause, looking forward to no final victory, filled only with love, faith and loyalty, they endured much and died for us.’

Thirty one sculptors entered the competition for a memorial design for the main facade of the building. Frederick Brook Hitch of Hertford was the winner. The panel over the entrance had to be removable, as the RSPCA only held a lease, not the freehold of Number 10 Cambridge Avenue.

RSPCA plaque on the outside of the Dispensary in Kilburn

A local paper recorded the official opening on 10 November 1932, by the Countess of Warwick. But the dispensary had been at work for over a year, during which time 6,000 animals had been treated. The ceremony was preceded by a meeting at St Augustine’s School in Kilburn Park Road, presided over by the Chairman of the RSPCA, Sir Robert Gower.

By the mid 1930s, more than 50,000 animals and birds had received attention at the Dispensary. At the rear of the well-equipped premises were glass fronted kennels and catteries with a loose box for horses. There was accommodation on site for vet and an assistant, providing 24 hour care. In 1936 alone, 9,756 animals passed through the doors.

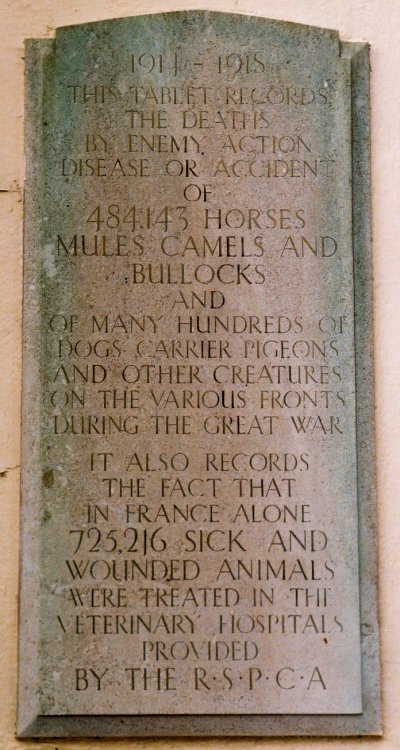

The RSPCA clinic at Cambridge Road is still open. The main door is flanked by two marble memorial panels. They record that 484,143 animals were killed by enemy action, disease or accident and that 725,216 animals were treated by the RSPCA during WW1. We now know the overall mortality figures were far higher, with an estimated 8 million horses dying in WW1.

The RSPCA clinic at Cambridge Road is still open. The main door is flanked by two marble memorial panels. They record that 484,143 animals were killed by enemy action, disease or accident and that 725,216 animals were treated by the RSPCA during WW1. We now know the overall mortality figures were far higher, with an estimated 8 million horses dying in WW1.

The horse is the animal most often associated with the European conflict. In 1914, the British and German armies had a cavalry force of some 100,000 men, but the development of trench warfare rendered cavalry charges unviable as a military tactic. But horses and mules were still needed to transport materials and supplies and to pull guns and ambulances. The animals also had to be fed, watered and tended. Strong ties developed between horse and rider. The Daily Mail on 31st December 1914, carried an article by a Welsh soldier serving in the Royal Field Artillery. He’d been with his horses for several years before war broke out. He said;

The horse is the animal most often associated with the European conflict. In 1914, the British and German armies had a cavalry force of some 100,000 men, but the development of trench warfare rendered cavalry charges unviable as a military tactic. But horses and mules were still needed to transport materials and supplies and to pull guns and ambulances. The animals also had to be fed, watered and tended. Strong ties developed between horse and rider. The Daily Mail on 31st December 1914, carried an article by a Welsh soldier serving in the Royal Field Artillery. He’d been with his horses for several years before war broke out. He said;

I could talk to them just as I am talking to you. There was not a word I said that they did not understand. And they could answer me – I was never once at a loss to know what they meant. Early in the retreat from Mons, a shell crashed right into the midst of the section with which I was moving. My gun was wrecked. I was ordered to help with another. As I mounted the fresh horse to continue the retreat, I saw my two horses struggling and kicking on the ground to free themselves. I could not go back to them, I tell you it hurt me. Suddenly a French chasseur dashed up to them, cut the traces, and set them at liberty. I was a good way ahead by then, but kept looking at them, and I could tell they saw me. Those horses followed me for four days. We stopped for hardly five minutes and I could not get back to them. There was no work for them but they kept their places in the line liked trained soldiers. They were following me to the very end. Whenever I looked, there they were in the line, watching me so anxiously and sorrowfully as to make me feel guilty of deserting them. Whether they got anything to eat, I do not know. I wonder if they dropped out from sheer exhaustion – I hope to Heaven it was not that. At any rate, one morning when the retreat was all but over, I missed them. I suppose I shall never see them again. That’s the sort of thing that hurts a soldier in war.

During the Gallipoli campaign, horses became so weak they collapsed and died in the mud and shell holes. When the New Zealand Forces were sent home, their horses were divided into three classes. Some mares were kept for breeding purposes; other horses were transferred to the British Army. Of the final group, many were destined to be butchered for meat.

Dead horses in 1918 (image copyright free via the Imperial War Museum)

Dogs accompanied sentries on patrol, carried messages and worked as scouts, ‘sniffing’ out the enemy ahead. Others acted as medics, sent onto the battlefield equipped with basic supplies that allowed a wounded man to tend to his own injuries. They might also stay with a fatally injured soldier until he died.

Pigeons were very reliable when it came to sending messages. It has been calculated that they had an astonishing 95% success rate getting through to their destination. The Government even issued a special ‘Defence of the Realm Regulation’ to prohibit the shooting of homing pigeons. Offenders were warned they faced six months imprisonment or a £100 fine.

A pigeon named ‘Cher Ami’ was awarded the Croix de Guerre for work in the American sector around Verdun in 1918. On her last mission, Cher Ami was shot but delivered a message that gave the co-ordinates of 194 soldiers cut off behind enemy lines. The men were rescued. Cher Ami recovered and was sent back to the USA where she died in 1919. Her body was put on display at the Smithsonian museum, Washington D.C.

There is newsreel footage of animals in service during WW1; but be warned many of them make for unpleasant viewing.

http://www.britishpathe.com/gallery/war-animals

http://www.theatlantic.com/static/infocus/wwi/wwianimals