Indiana Jones and the West Hampstead conman

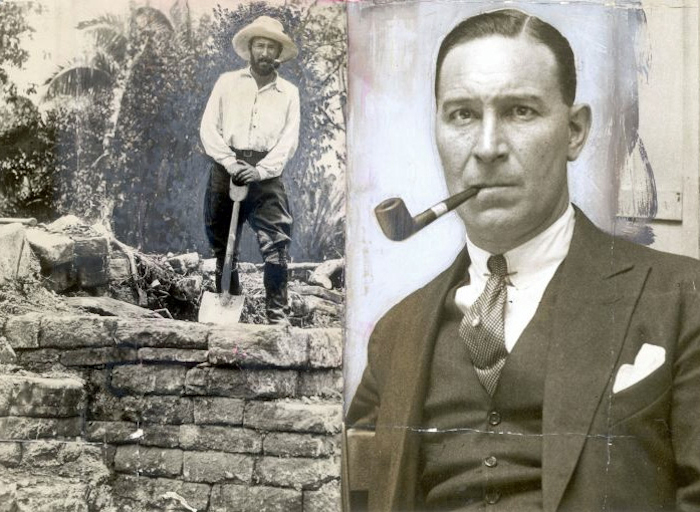

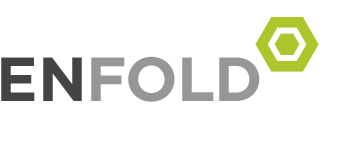

Mitchell Hedges in adventurer and gentleman guises

In 2008’s Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, there is a brief mention of a real person. Our eponymous hero says that while he was studying at the University of Chicago, he was fascinated by the work of a man called Mitchell Hedges, a real-life adventurer and explorer who found a crystal skull. Although the writers of the film say they did not use Mitchell Hedges as a model for Indiana Jones, there are some interesting parallels between the real and the fictional characters – and a link with a West Hampstead conman.

Hedges was born in Islington in 1882 as Frederick Albert Hedges, the son of a dealer in gold, silver and diamonds. He added ‘Mitchell’ from a family name on his mother’s side and to his friends he was known as Mike, Midge or Mitch Hedges.

Young Frederick was educated at Berkhampstead prep-school in Cheltenham before moving to University College School in 1896 (the school was in Gower Street then, moving to its present site to the north of West Hampstead in 1907). He left school at 16 and joined a copper-prospecting expedition to Norway. When he returned to London, he briefly worked as a clerk in the stock exchange before going to New York at the end of 1901. After nearly five years in America he returned, and lived at 42 Kensington Park Gardens, Notting Hill Gate. In November 1906 Frederick married Lilian Agnes ‘Dolly’ Clarke. They had no children and with all his travelling she often did not see him for long periods. Frederick started a stock-broking business in partnership with others, but he went bankrupt in 1912.

After this failure Mitchell Hedges travelled extensively and lived a colourful life. He claimed he was captured in Mexico by the revolutionary Pancho Villa in 1913. In October 1914, he had an illegitimate son, Frederick Joseph, born at the Paddington home of the child’s mother, Mary Florence Stanners. Three years later, he was back in North America and claimed he met Trotsky in New York. He also adopted ten-year-old Anne-Marie ‘Anna’ Le Guillon, the orphaned daughter of some friends from Ontario.

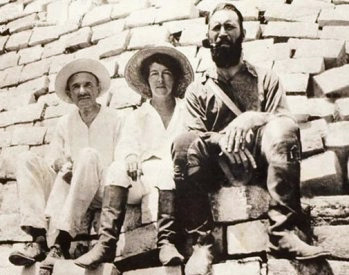

Hedges met Lady Richmond Brown, who was separated from her husband (their marriage was annulled in 1930 on the grounds of Lady Brown’s adultery with Hedges), and the two travelled together on several Indiana Jones-style expeditions funded by Lady Brown and London newspapers. In the 1920s they were in British Honduras (today’s Belize) with archaeologist Thomas Gann and in 1924 they visited Lubaantun on the Rio Grande in the south of the country. This is a ruined Maya city dating from the 8th and 9th centuries. Hedges later claimed he had discovered the city, but Gann had actually discovered them more than 20 years earlier.

Mitchell Hedges and Lady Richmond Brown at Lubaantun

The Hold Up on the Ripley Road

By 1927, Mitchell Hedges had became famous, writing about his adventures in newspaper articles and books. On 14 January he had a busy day in London lecturing to Bank of England employees and doing a radio broadcast. He dined at the National Liberal Club and was being chauffeured to his home at Sandbanks Parkstone near Bournemouth, accompanied by his friend Colin Edgell.

On Ripley Road in Cobham Woods, Surrey, the car was stopped by a man waving them down in the headlights. He said his friend was injured and needed to go to hospital. Kenneth Taylor, the young chauffeur went to help and when he did not return Hedges and Edgell went to look for him. They were astonished to find Taylor lying by the side of the road with his hands tied behind his back. Suddenly, they were set upon by six men but after a fight their attackers ran off into the darkness. Returning to the car Mitchell Hedges found his brief case containing papers and six shrunken heads had been stolen. Before returning to London the three men drove to Guildford police station to report the theft.

The day after the robbery, Hedges received a letter at his usual suite at the Savoy Hotel that said the entire escapade had been a hoax. The writer said that he and five other young Liberals had objected to Hedges’ remarks in a recent speech at the National Liberal Club, where he spoke about the lack of grit in the British youth of today. “You did not suspect that the six ruffians who attacked you in Cobham Woods were six of these very weaklings whom you were reviling with their lack of enterprise and pluck.” His bag was returned intact and Hedges said he accepted it as practical joke.

There the matter appeared to rest, but a week later, an article appeared in the Daily Express followed by another in the Sunday Express that included an interview with the gang’s ring-leader, Clifford Bagot Gray. The articles said that Hedges had colluded with the young Liberals to gain further notoriety for himself and to help drive publicity for Bagot Gray’s ‘Monomark’ monogram service.

Hedges sued the papers for libel and the case was heard in the High Court in February 1928. The defence barrister pressed Hedges hard, claiming he was an ‘impostor’ who had exaggerated his exploits in his publications. Witnesses were called who had taken part in the hoax, saying it had been rehearsed several weeks earlier in Cobham Woods. The jury, without leaving the box, found in favour of the defendants and Mitchell Hedges lost the case and was ordered to pay costs.

The West Hampstead connection

On 12 February, 1928, during the trial, Mitchell Hedges was contacted at the Savoy by a Major MacAllan who said he could help with the case. A meeting was arranged and MacAllan was accompanied by a man he introduced as his solicitor Mr Astor. He claimed to have met Mitchell Hedges in Buenos Aires where he was the head of the MacAllan Construction Company. “You are in a hell of mess and you are going to lose your case. I want to do the best I can to help you,” said MacAllan.

It was suggested that if the verdict went against him, Hedges could lose all his friends and be ostracized. MacAllan said that he had helped people in previous high profile libel cases, for a fee. Even better, as his cousin was on the jury they could win the case, but it would cost Hedges £1,000. After they left, Hedges immediately contacted Scotland Yard. A second meeting was arranged for the next day. Four detectives hid in a small adjoining box-room listening on headphones to a microphone hidden in Mitchell Hedges’ Savoy sitting room. When MacAllan asked for £500 now and £500 the following day, the detectives rushed into the room and arrested him and Mr Astor.

In court the men were identified as James MacAllan (who was not a major), 59, a civil engineer of Dennington Park Road and Frederick George Arnold (a.k.a. Mr Astor), 60, a fancy toy dealer of Tachbrook Street in Pimlico. They pleaded guilty to attempting to obtain money by false pretences, and were each sentenced to six-months imprisonment with hard labour.

A serial conman

Information on the Dennington Park Road conman is scant. Before World War I, he had worked as a civil engineer in Argentina and by 1928 he was a secretary for the London and Provincial Greyhound Racing Association. But he became a career conman, sentenced to 12-months imprisonment in October 1926 for defrauding five people by claiming valuable mineral deposits in Yorkshire. There were numerous complaints that he had run up debts with tradesmen pretending to be a major. In February 1927 he received a four-month sentence for stealing £250 from a woman he had promised to marry.

Nine years after the Hedges incident, he was in court again, charged with obtaining £125 by false pretences from Elsie May Andrewartha of Vincent Square, Westminster. This was a callous case. Miss Andrewartha was a nurse who attended MacAllan while he had an operation on his leg in Westminster Hospital. After he was discharged in October 1936, she cared for him at his home. MacAllan told her he was an engineer with a secretary and two offices and that he was working on a big scheme at the Brighton seafront involving the mayor and worth £3 million. He offered Elsie the opportunity to invest in the syndicate he was forming. In November and December 1936 she gave him two cheques totalling £125.

She did not see him again until June 1937, when he told her the Brighton scheme had failed because they could not raise enough money. However, he reassured her that he was now working on another project in Huddersfield where he had invested her money. Miss Andrewartha was very annoyed and asked for her money back. In court the police said MacAllan was a persistent and very dangerous man, and they had received numerous complaints of fraud about him. He was found guilty and sentenced to 18 months.

Who was the ‘Major’?

His full name was James Cator Scott MacAllan and he was probably born in Scotland about 1868. He was separated from his wife and lived at several London addresses with his daughter Marjorie (born in 1897) who was a shop assistant. At the time of the attempted con of Mitchell Hedges in February 1928 he was living in Dennington Park Road. In 1933, he and Marjorie were in Christchurch Road Streatham, but by 1936 they had moved back to West Hampstead – living at 16 Fairhazel Gardens. During the war they lived at 5 Fordwych Road, before Marjorie moved to Hendon. By 1947 James MacAllan was living on his own at 6 Thayer Street in Marylebone and the following year he was renting a single room at 24 Nelson Square, Southwark. He died at the end of 1948 in Westminster.

What about that crystal skull?

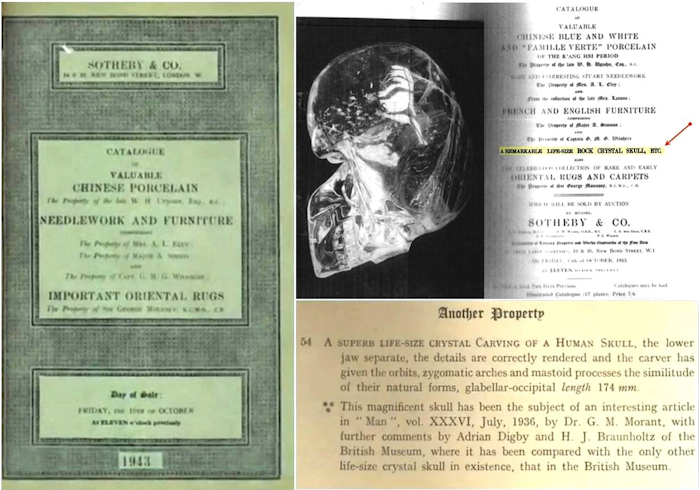

Mitchell Hedges wasn’t averse to some deceit himself. He and his adopted daughter Anna claimed they found their famous 3,000-year-old Mayan crystal skull at Lubaantun on her 17th birthday – January 1st, 1924. In fact Frederick bought the skull in auction at Sotheby’s on 15 November 1943 for £400 (about £1,600 today).

Skull in Sotheby’s Catalogue 15 Oct 1943

Recent research by Jane MacLaren Walsh, from the Smithsonian Institute in Washington DC, has looked at Eugène Boban, a key figure who owned several crystal skulls that were probably made for him in Mexico. This French antiquarian worked for several years in Mexico and exhibited two crystal skulls in Paris in 1867. In the 1870s he opened a shop in Paris selling Mexican artefacts before moving to New York in 1885. The following year Tiffany and Co. bought one of his skulls at auction for $950 and sold it in 1898 to the British Museum at the original price.

Some time before 1934, Sir Sidney Burney, a London antique dealer, purchased another crystal skull, almost identical to the one the British Museum bought from Tiffany’s. Jane MacLaren Walsh believes it was based on the one in the British Museum and probably made in Europe between 1910 and 1930, and that Boban, who died in 1908, was not directly involved with this second skull.

There is no information about how Burney acquired his skull, but it is very similar to that in the British Museum, with more detailed modelling of the eyes and teeth, and a separate lower jaw. In fact this was the skull bought by Mitchell Hedges at Sotheby’s. Despite his claim to have found it at Lubaantun in the 1920s, he first mentions it as a ‘new acquisition’ in a letter to his brother dated 1943.

When confronted about this discrepancy, Hedges said he had given the skull to a friend, who put it up for auction at Sotheby’s, so he bought it back. This far-fetched explanation is typical of the stories he made up and included in his biography, Danger is My Ally, published five years before he died of a stroke in Devon in June 1959. His daughter Anna exaggerated the story further and claimed alien and supernatural powers for the ‘Skull of Doom’ which she periodically exhibited. In fact there is no evidence that Anna went to Lubaantun in the 1920s and she simply inherited the skull after her father died. Anna herself died in 2007 aged 100, and the huge mythology about the powers of the skull has continued to flourish. Today, the skull is in the possession of her close friend Bill Homann.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!