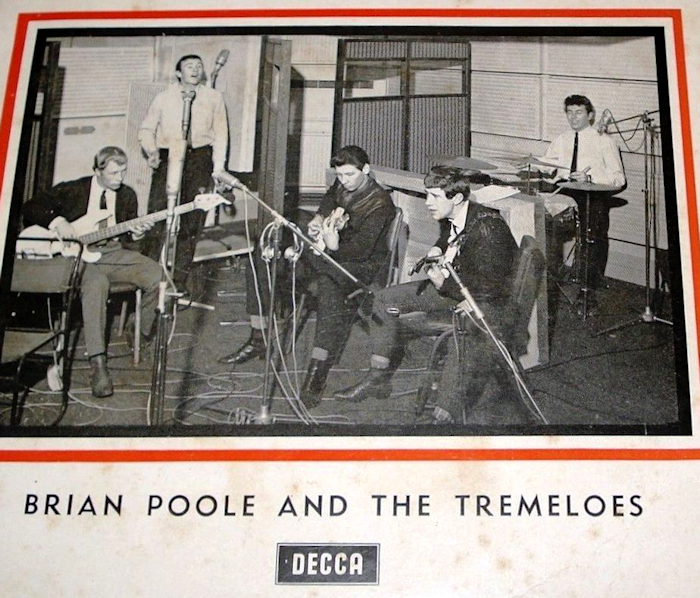

Our next book, ‘Decca Studios and Klooks Kleek’ will be published by The History Press in November 2013. This is the first history of Decca Studios, which were in Broadhurst Gardens from 1937 to 1980 and where thousands of well-known recordings were made. From 1961 until it closed in 1970, Klooks Kleek was the famous jazz and blues club run by Dick Jordan and Geoff Williams on the first floor of the Railway Hotel, next to the Decca Studios.

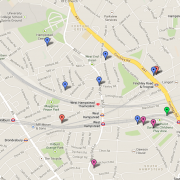

This blog is the first of two stories about music in West Hampstead and Kilburn. The area has a surprisingly rich history of music. The first instalment looks at music production and the recording studios and record companies who operated here. The second, to be published later, will cover the many musicians who lived there.

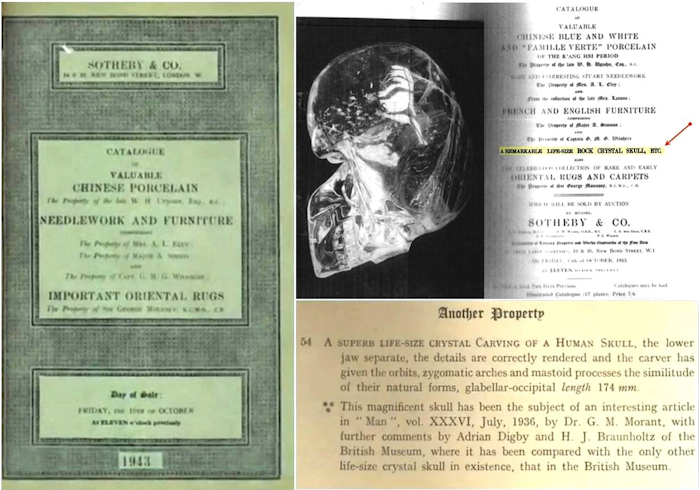

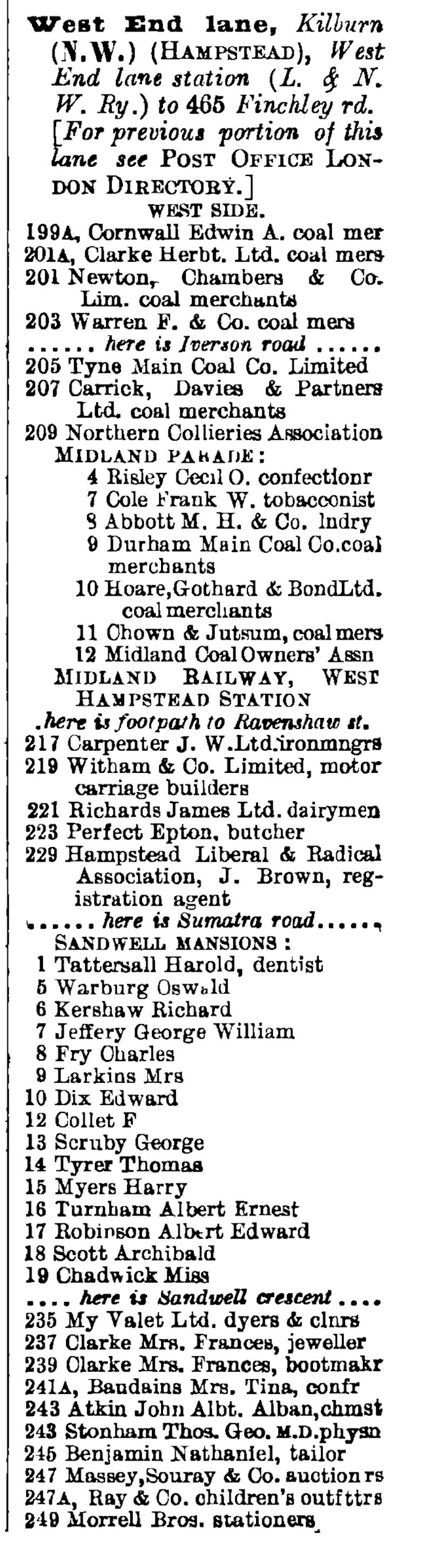

The Crystalate Gramophone Record Manufacturing Company

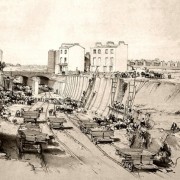

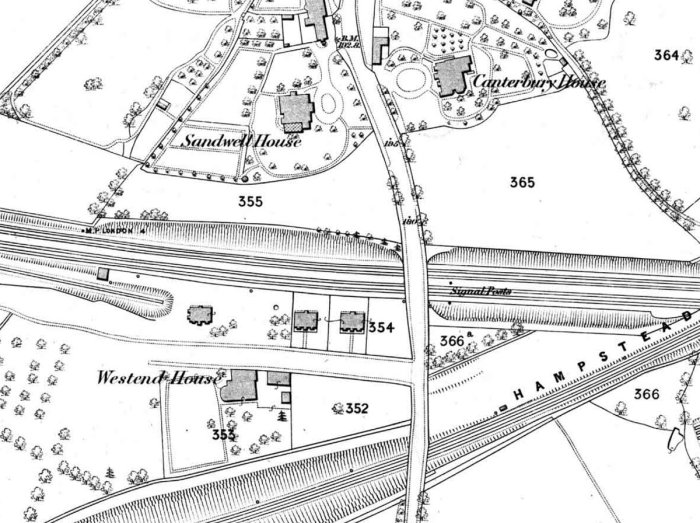

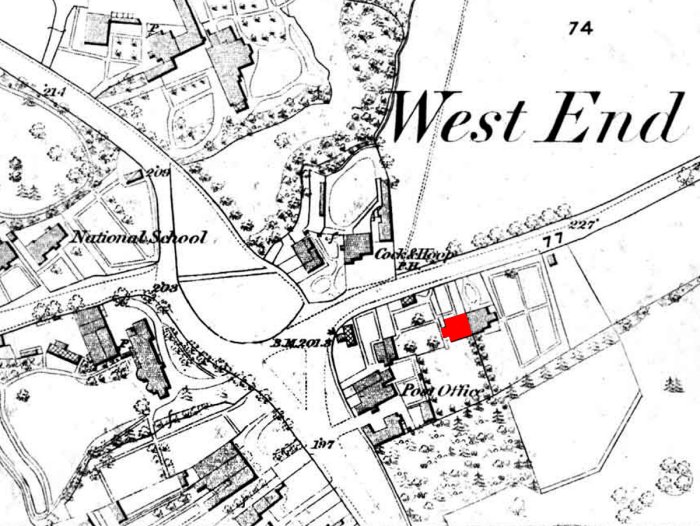

Crystalate took over West Hampstead Town Hall in Broadhurst Gardens in 1928 and moved their recording studio there. That year the Crystalate Manufacturing Company appears at 165 Broadhurst Gardens for the first time in the phone book. Today the building is used by English National Opera.

In August 1901 the Crystalate Company was founded at Golden Green (note, not Golders Green), Haddow, near Tunbridge in Kent , by a partnership of a London and an American firm. The British company had begun by introducing colours into minerals and making imitation ivory. The American company which had made billiard balls and poker chips started making gramophone records from shellac. In July 1901 the American George Henry Burt, applied for a trademark on the word ‘Crystalate’ for all their plastic products. The secret formula to make Crystalate substances was kept in a sealed iron box which required two keys to open it. Burt had one and Percy Warnford-Davis, the English director, had the other. It is said that Crystalate made the first records to be pressed in England in 1901/2; but there is no direct evidence of this apart from the 1922 recollections of Charles Davis, the works manager.

In 1926 they moved their office and recording studio from 63 Farrington Road to Number 69 which was named ‘Imperial House’ after one of their record labels. In 1929 they moved again to 60-62 City Road which they called ‘Crystalate House’. T he company made records for some of the very early labels such as Zonophone, Berliner and Imperial. Crystalate also produced large numbers of records for Woolworths under various budget labels, including Victory and Rex. At first they cost a shilling which represented very good value for the enormously popular artists of the day such as Gracie Fields, Larry Adler, Billy Cotton and Sandy Powell. Also on the label were American stars: Bing Crosby, the Mills Brothers, the Boswell Sisters, and Cab Calloway.

During the Depression many of the record companies ran into financial trouble and they were bought up by either EMI or Decca. In March 1937 the record side of Crystalate was sold to Decca for £200,000, or about £10 million today. The Crystalate engineers were very relieved when they found out Decca had decided to close their existing studio in Upper Thames Street and move to Broadhurst Gardens.

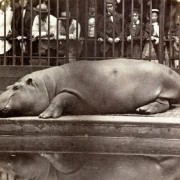

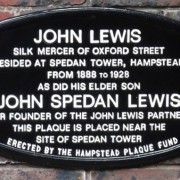

Decca Studios, today used by English National Opera

Decca Studios

The Decca studios were in Broadhurst Gardens from 1937 to 1981 and our new book will provide a detailed history. Stars such as The Rolling Stones, David Bowie, Marc Bolan, Billy Fury and the Moody Blues were recorded here. On 1st January 1962 the Beatles auditioned at the studios, but after travelling down from Liverpool in a van, they’d gone out to celebrate New Year’s Eve, and their playing did not impress Decca. Other labels also turned them down until EMI Parlophone, Decca’s great rival, signed them in June 1962. The Beatles first single, ‘Love Me Do’ was released on 5 October 1962 and peaked at Number 17 in the charts.

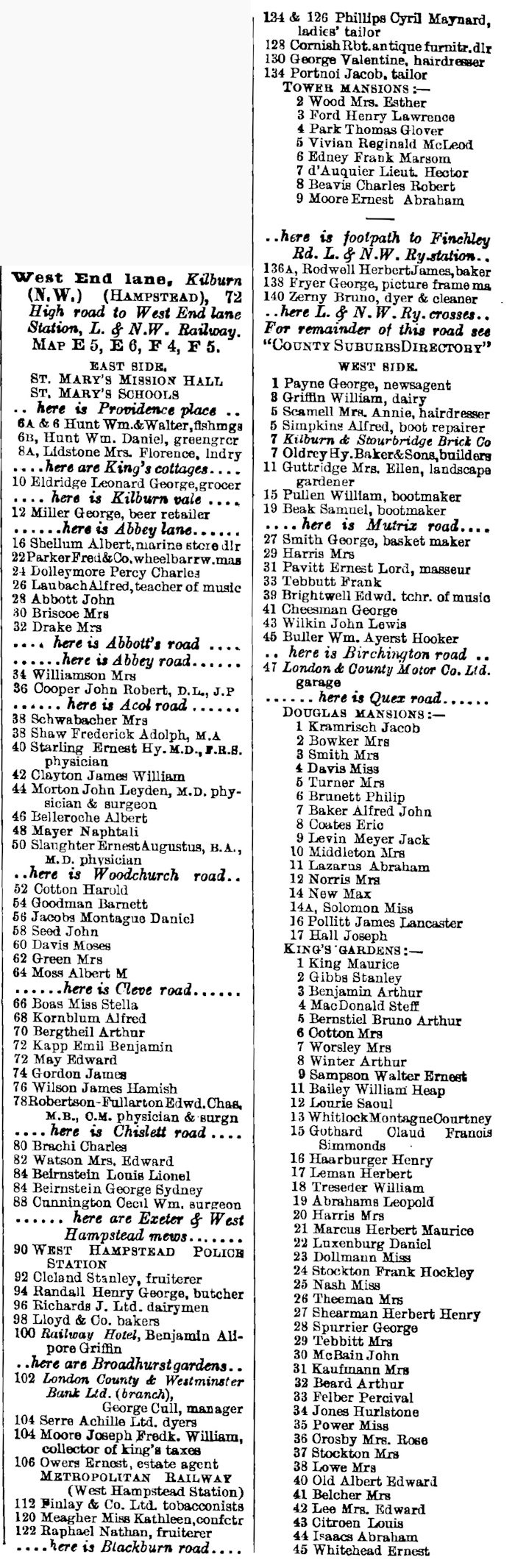

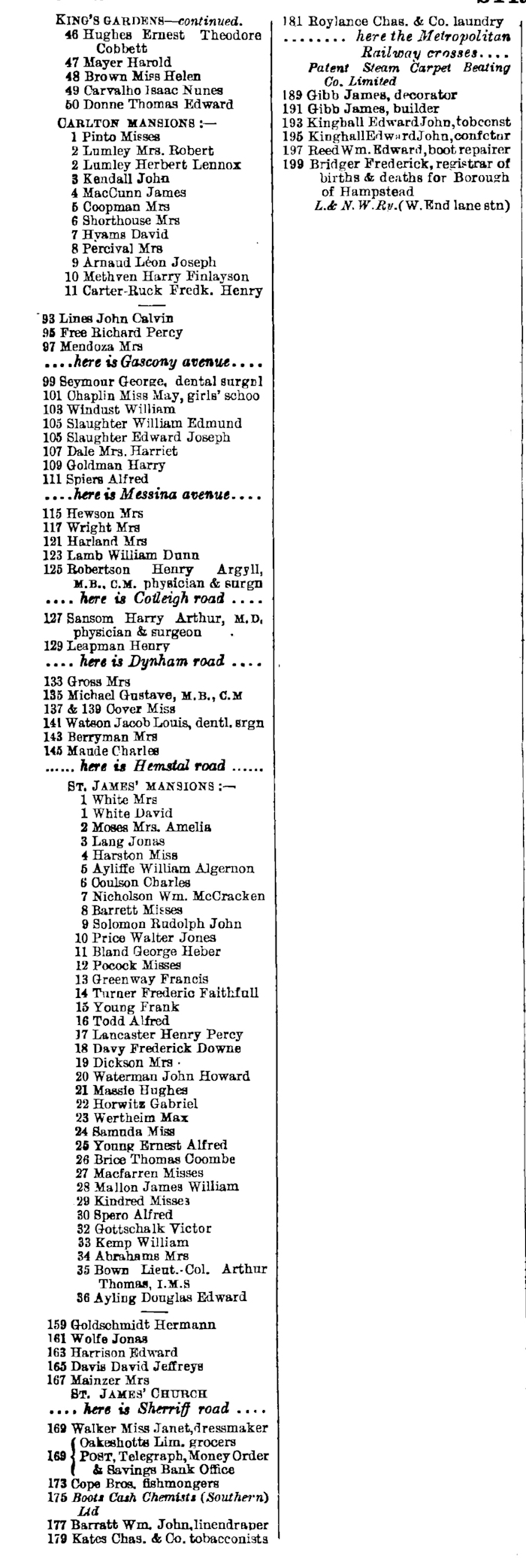

Gus Dudgeon, engineer and producer Lymington Mansions and Kings Gardens, West End Lane

When he left school Gus (Angus) had several short-term jobs before he got a job as the tea boy and junior assistant at Olympic Studios near Baker Street. He was ‘blown away’ by the power of the studio speakers with their tremendous bass and treble ranges. Desperate to play with the controls he said ‘I was terrified at the idea of ever getting onto the recording console.’ But he managed to get a job as an engineer at Decca Studios in 1962. At the time Gus was sharing a flat at 2 Lymington Mansions in West Hampstead where he stayed until 1965. The blues singer Long John Baldry slept on a bed in the hallway.

During his five and a half years at Decca Studios, Dudgeon engineered the Zombies’ hit ‘She’s Not There’ (1964) and the celebrated John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers with Eric Clapton (1965), known as the Beano album from the cover, where Eric is pictured reading a copy of the comic. Early sessions included recordings for Marianne Faithfull with producer Andrew Loog Oldham and session guitarists Jimmy Page and John Paul Jones, later of Led Zeppelin.

His first co-production credit came in 1967 with the debut album of Ten Years After. A year later, encouraged by Rolling Stones manager Andrew Loog Oldham, he left Decca to found his own production company. He worked on all the classic recordings by Elton John, including such hits as ‘Your Song,’ ‘Rocket Man,’ and ‘Goodbye Yellow Brick Road’. In 1969, he produced David Bowie’s first hit, ‘Space Oddity,’ and later, albums by such artists as Chris Rea, Lindisfarne, and XTC.

In the 70s Gus joined Elton John and formed Rocket Records. In the early 80s he built SOL Studios in Cookham Berkshire which he later sold to Jimmy Page.

From 1967 till 1973 Gus lived at 3 Kings Gardens in West End Lane. He then moved to Surbiton. The record world was shocked in July 2002 when Gus Dudgeon and his wife Sheila were killed in a car crash.

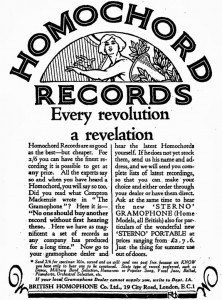

British Homophone, 84a Kilburn High Road

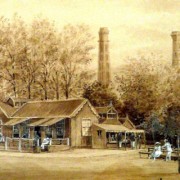

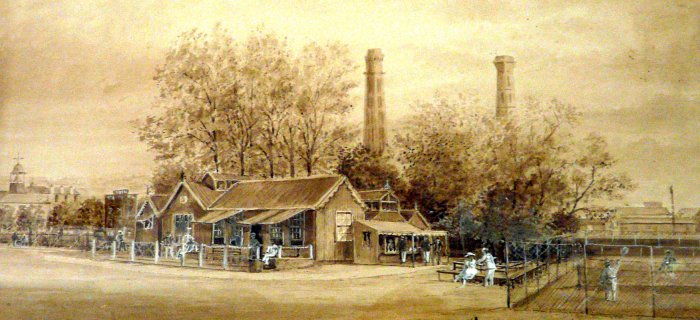

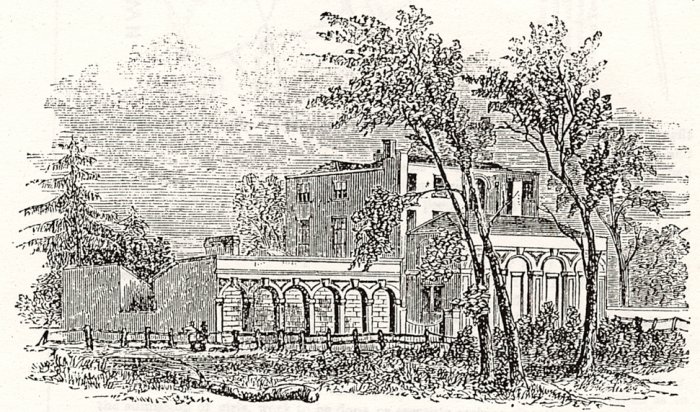

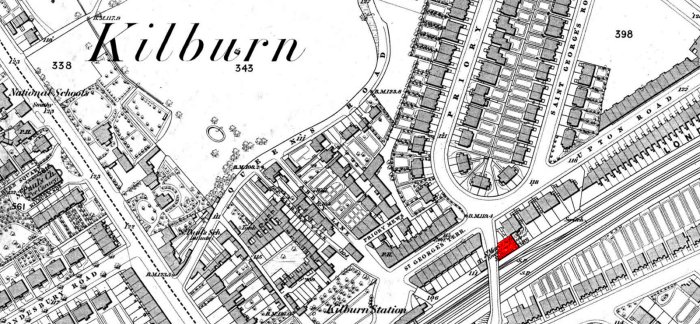

This building was behind the present Sainsbury’s in Kilburn High Road. Before British Homophone opened their recording studio there in 1929, it was the site of a large house called St Margaret’s.

The last owner and occupier of St Margaret’s was the builder Robert Allen Yerbury who rented the house about 1877. He soon bought the freehold as well as a large piece of land adjoining his grounds and built Colas Mews (behind the present Iceland store). He then used the garden in front of the renamed St Margaret’s Lodge as the site for a terrace of shops. Although completely hemmed in by the shops on the High Road, Yerbury was able to rent the house to a series of tenants.

By 1903 a hall and conservatory had been added to the back of St Margaret’s Lodge. ‘Professor’ Sidney Bishop ran ‘The Athenaeum’ for dancing there from 1902 to 1914. During WWI it was used as a forces recreation room and in the 20s the Hall became the Kilburn branch of the Church Army, with successive secretaries living in the old Lodge.

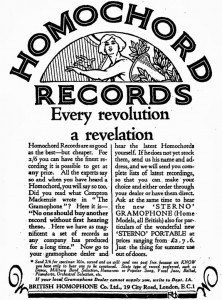

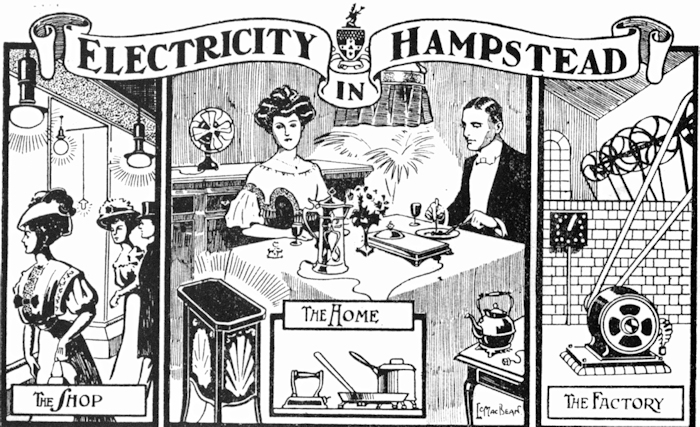

The site was next adapted as a recording studio for the British Homophone Company Ltd. William Sternberg was the director of a company that had been selling gramophones under the trade name of Sterno for some years. They had used the masters and distributed records of the Homophon Company of Berlin since 1906, and also produced Sterno records from 1926 to 1935. On 24 May 1928 the Times announced that British Homophone was issuing a share capital of £150,000. In a contract dated 21 May 1928 , Sternberg put all his assets into the new company of British Homophone, for £37,500 worth of shares. They moved into 84a Kilburn High Road the following year.

British Homophone advert, 1928

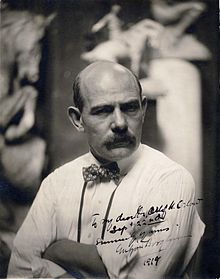

Lots of well known performers and dance bands of the time were on the Sterno label including Mantovani, Oscar Rabin, and Syd Lipton. The most important artist on the label was the pianist and band leader Charlie Kunz who was selling an astonishing one million records. He became the highest paid pianist in the world earning a £1,000 week. Born in America , he came to England in 1922, and during the 1930s he lived in Dollis Hill.

Charlie Kunz record on the Sterno and British Homophone label

In 1934 the BBC studios in Maida Vale sent recordings by telephone lines to British Homophone in Kilburn who recorded them onto wax discs. They were able to offer the BBC a quick turnaround of 12 hours for programme repeats.

But like other companies in the Depression, British Homophone struggled financially and in May 1937 Decca and their rival EMI jointly purchased all the British Homophone masters for £22,500. When British Homophone left Kilburn in 1939, the ladies clothing chain, Richard Shops, who had been at Number 82 since 1936, took over Number 84 and probably the studio as well.

William Sternberg lived at ‘Mondesfield’, in Exeter Road Kilburn, from 1924. When he died on 14 June 1956 , his addresses were Exeter Road and Seddscombe , Sussex . He was buried at the Willesden Liberal Jewish cemetery probably with his wife Eva who died in 1925. He was a wealthy man and left £19,379, today worth about £900,000.

Sterno and Canned Heat

As an interesting aside, Sterno was also the name of an American campsite cooking fuel made from jellied alcohol. During the Depression, and strained through cloth, it was used as a cheap substitute for whisky and popularly known as ‘Canned Heat’. The early bluesman, Tommy Johnson, wrote and recorded ‘Canned Heat Blues’ in 1928, and the famous American band Canned Heat, which was formed in Los Angeles in 1965, took their name from the song.

The Banba

The studio building was used from 1951 to 1968 by Michael Gannon who ran the famous and very poplar Irish dance hall there called ‘The Banba’ (taken from a poetic name for Ireland ). In 1971 the property was demolished with Sainsbury’s redevelopment of the entire site. Marianne can remember being taken to the Banba. She was bought a coffee made from Camp Coffee Essence, which Wikipedia describes as: A glutinous brown substance which consists of water, sugar, 4% caffeine-free coffee essence, and 26% chicory essence. She left it untouched after the first sip.

British Homophone after the buyout

Despite the 1937 buyout by Decca and EMI, the British Homophone name continued into the early 1980s, but was no longer based in Kilburn. By 1962 it was at Excelsior Works, Rollins Street, SE15, New Cross. The new company pressed some of the early records for Chris Blackwell’s Island Records about 1965. Edward Kassner the boss of President Records owned the pressing plant. Eddy Grant and ‘The Equals’ were signed with President Records. Eddy set up Ice Records and a studio called the Coach House and bought the pressing plant in New Cross from Kassner in the late 1970s, where he pressed his own records until the early 1980s, when he left England.

Island Records, 108 Cambridge Road

Island Records was formed by Chris Blackwell who was born in London, but grew up in Jamaica. In 1958 after trying various jobs and using money from his parents, he decided to record Lance Hayward, a young, blind jazz pianist who was playing at the Half Moon Hotel in Montego Bay. The record was released in 1959, and this was the beginning of what would later become Island Records. The following year Blackwell had a hit with Laurel Aitken’s ‘Boogie In My Bones’. Using the money from the sales he set up a small office in Kingston. In 1962 Blackwell moved to London and began selling records to the West Indian communities in London, Birmingham, and Manchester from the back of his Mini-Cooper.

Blackwell took the name of Island Records from Alec Waugh’s novel ‘Island in the Sun’. Island Records Ltd began in May 1962 with four partners who invested a total of £4,000: Chris Blackwell, Graham Goodall, an Australian music engineer living in Jamaica, the Chinese-Jamaican record producer Leslie Kong and his brother.

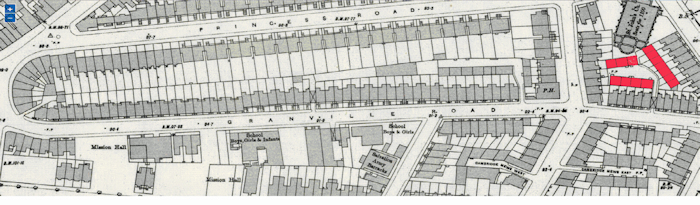

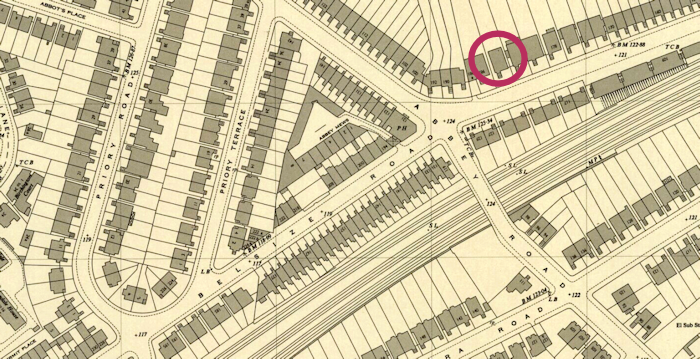

From March 1963 to 1967 Island Records had their office at 108 Cambridge Road , since demolished as part of the South Kilburn redevelopment plan. Originally a barber’s shop run by the Gopthal family, when accountant Lee Gopthal bought the house, he rented it out. Chris Blackwell converted the premises into offices managed by David Betteridge, who was later made a director of Island. Initially the records were pressed by British Homophone and then at the Phillips factory in Croydon. In 1962, the basement store at 108 had been a recording studio set up by Sonny Roberts of Planetone Records. Blackwell introduced additional labels such as Black Swan, Jump Up, Aladdin, Surprise, Sue Records and Trojan which was run by Lee Gopthal .

Rob Bell describes his time at Island from 1965 to 1972 in a series of articles. See www.trojanrecords.com. He said that Island were releasing about half a dozen records a week. The new release sheets were printed by Mr Reed who had a small print shop a few doors up Cambridge Road. Rob said he and others used to eat at Peg’s Café over the road and drink at The Shakespeare pub next to the office. In 1968 when business picked up with the popularity of reggae, together with the compulsory purchase for the South Kilburn redevelopment, Island moved to the much larger Music House at 12 Neasden Lane.

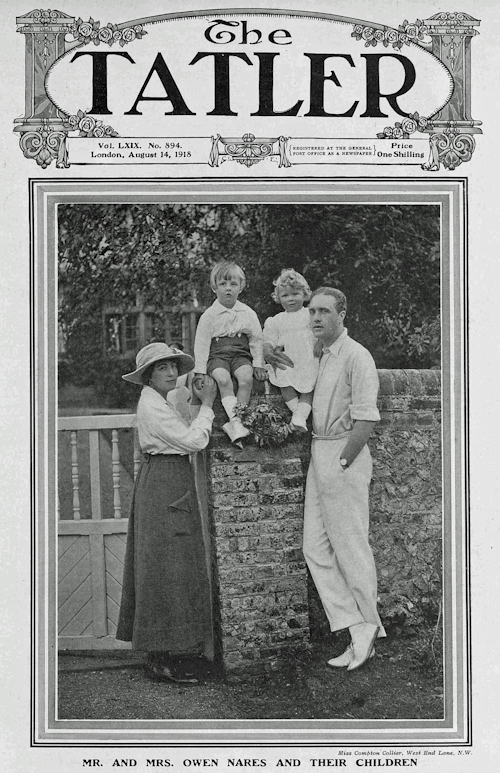

In 1963 Blackwell decided to bring the fourteen year old Millie Small to London. Looking for a suitable song for her to record, he found a copy of American singer Barbie Gaye’s ‘My Boy Lollipop’ which he had bought five years earlier in New York. Recorded at Olympic Studios with a ska arrangement, the record was leased to the Phillips’ Fontana label and in 1964 it sold six million copies worldwide. It reached Number 2 in the UK and the US and became the first international Jamaican hit. Marianne heard Millie sing the song at one of the regular Saturday morning music sessions at the Kilburn State , held in their dance hall with an entrance in Willesden Lane.

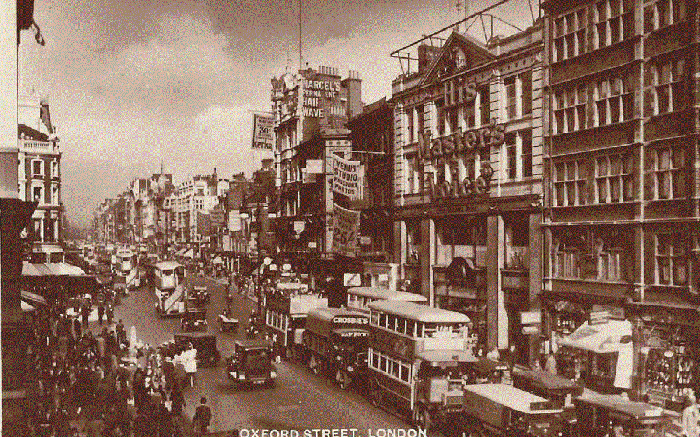

Other successful records followed with Jimmy Cliff and the Birmingham band, the Spencer Davis Group who had several hits leased to Fontana such as, ‘Keep On Running’ (1965) and ‘Gimme Some Lovin’. Building on these hits, Island moved to new offices at 155 Oxford Street. In 1970 they moved again to Notting Hill where they had established their own studio in a former church at 8 -10 Basing Street. From here they expanded massively, with artists such as Bob Marley, Cat Stevens, Fairport Convention, Free, Traffic, Jethro Tull, Grace Jones and U2.

In 1989 Blackwell sold his stake in Island and eventually resigned in 1997. His mother Blanche was Ian Fleming’s longtime lover and Blackwell now owns the writer’s house, Goldeneye, in Jamaica . He bought it from Bob Marley. For a beautifully illustrated book see, ‘The Story of Island Records’, edited by Suzette Newman and Chris Salewicz (2010).

Ritz Records, 1 Grangeway

Grangeway is the small road leading off the Kilburn High Road into the Grange Park. Mick Clerkin ran Ritz Records here which began in about 1981. They produced Irish records and had big hits with Joe Dolan and Daniel O’Donnell. Clerkin had previously worked as a roadie for the popular Mighty Avons Showband, and then in 1968 he set up Release Records. Ritz were still at Grangeway in 1996 but had moved to Wembley by 2000. The company went into liquidation in 2002.

New building in Grangeway today, the site of Ritz Record

Master Rock Studios, 248 Kilburn High Road

In January 1986 Steve Flood and Stuart Colman opened their studios in Kilburn High Road. Stuart Colman was a musician who produced hits for Shakin’ Stevens, The Shadows, Kim Wilde, and Alvin Stardust. He also worked as a presenter at the BBC before opening Master Rock Studios. Flood and Colman were soon joined by studio manager Robyn Sansone who came from New York. An amazing number of musicians were recorded here including: Elton John, Jeff Beck, U2, Eric Clapton, Roxy Music, Simply Red and Suede. The music for the film ‘The Krays’ was also recorded at Master Rock.

They wanted the very best quality recording equipment so they bought a Focusrite console. Focusrite was founded in 1985 by Rupert Neve and the Forte console was developed in 1988. The idea was simply to produce the highest-quality recording console available at the time, regardless of cost. But the prohibitively expensive design limited the production to just two units, after which Focusrite got into financial difficulties. One console was delivered to Master Rock Studios in Kilburn and the other to the Electric Lady Studio in New York .

The Focusrite Forte console at Master Rock Studios

Bernard Butler the guitarist with Suede who recorded at Master Rock said: “Master Rock Studios was originally haunted by buying one of the only custom made Focusrite consoles. It arrived several months late so left them without business for a long time and despite being used on everything after it arrived, I don’t think they recovered.”

Bernard was right. Despite the Master Rock Studios being busy, there were financial problems and in 1991 the business was put up for sale. Douglas Pashley bought it and became the CEO in 1992. But problems continued and eventually they closed in June 2000. Number 248 Kilburn High Road has since been demolished.

248 Kilburn High Road today, site of Master Rock Studios

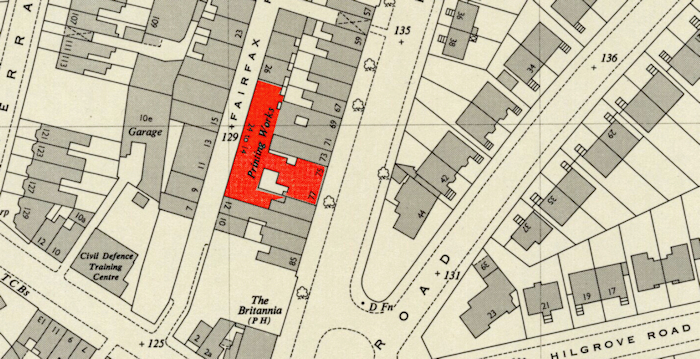

West Heath Studios, 174 Mill Lane

The composer and conductor Robert Howes, who worked with Alan Parsons and Eric Woolfson on the Alan Parsons Project, said he was doing lots of work in different studios and decided that he needed to build his own. He had previously lived in Welbeck Mansions and knew the West Hampstead area. He found a building in West Heath Mews which ran along the top of a row of garages, and set up his studio there at the end of the 1980s to record his music for TV. He did ‘Songs for Christmas’, the theme music for Kilroy and Rescue and lots of other programmes. Then he leased the studio to Eric Woolfson who later built his own studio in Cricklewood Lane . Woolfson had met Alan Parsons at the Abbey Road studios where Parsons had recorded Pink Floyd’s ‘Dark Side of the Moon’.

West Heath Studios, 2013

West Heath Studios is currently owned by Edwyn Collins who took it over in 1995. Edwin was born in Scotland and had hits with the Glasgow band Orange Juice. His major success was ‘A Girl like You’ which became a worldwide hit in 1994. After he and his wife Grace moved to Kilburn, Edwyn suddenly had a stroke in 2005 which left him paralysed. But he has since made a remarkable recovery and started to perform again. His cofounder and recording engineer Seb Lewsley kept the studio going. Edwyn’s friend Bernard Butler who lived locally in Fawley Road, recorded Duffy’s Rockferry album (2008) at West Heath. Edwyn recorded his latest album Loosing Sleep at the studio in 2010.

Have a look at YouTube for some amusing episodes of ‘West Heath Yard’.

Shebang Studio

This was a small studio in Coleridge Gardens, a mews off Fairhazel Gardens, run by Nigel Godrich. Nigel is a recording engineer and producer, best known for his work with the band Radiohead. He has also worked with Paul McCartney, Travis, Natalie Imbruglia, U2 and REM. Bernard Butler said, “Nigel Godrich’s studio was off Fairhazel Gardens where it meets Belsize Road and was called Shebang. He shared it with Sam Hardaker and Henry Binns who later became Zero 7. They were all assisting / engineering at RAK Studios at the time, which is where Radiohead and I met Nigel.” RAK Studios is in St John’s Wood and was started by Mickie Most in 1976.

The next blog story will look at the musicians who lived in West Hampstead and Kilburn.

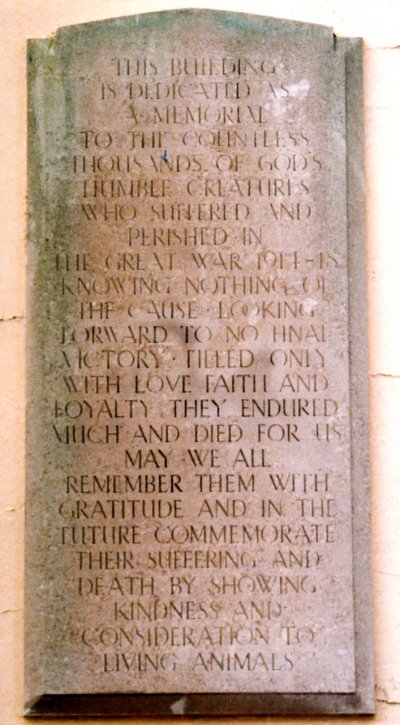

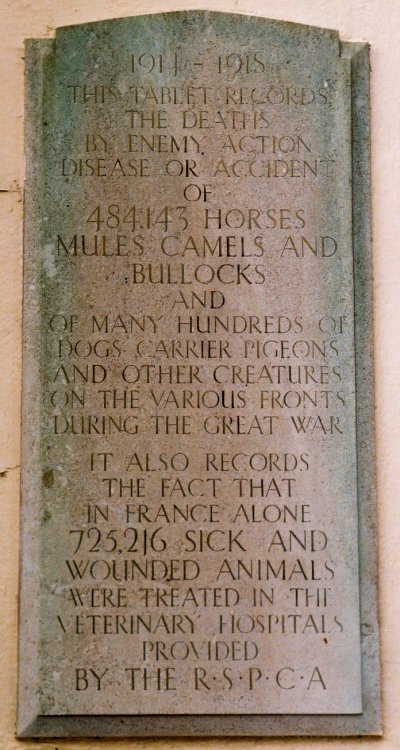

The RSPCA clinic at Cambridge Road is still open. The main door is flanked by two marble memorial panels. They record that 484,143 animals were killed by enemy action, disease or accident and that 725,216 animals were treated by the RSPCA during WW1. We now know the overall mortality figures were far higher, with an estimated 8 million horses dying in WW1.

The RSPCA clinic at Cambridge Road is still open. The main door is flanked by two marble memorial panels. They record that 484,143 animals were killed by enemy action, disease or accident and that 725,216 animals were treated by the RSPCA during WW1. We now know the overall mortality figures were far higher, with an estimated 8 million horses dying in WW1.  The horse is the animal most often associated with the European conflict. In 1914, the British and German armies had a cavalry force of some 100,000 men, but the development of trench warfare rendered cavalry charges unviable as a military tactic. But horses and mules were still needed to transport materials and supplies and to pull guns and ambulances. The animals also had to be fed, watered and tended. Strong ties developed between horse and rider. The Daily Mail on 31st December 1914, carried an article by a Welsh soldier serving in the Royal Field Artillery. He’d been with his horses for several years before war broke out. He said;

The horse is the animal most often associated with the European conflict. In 1914, the British and German armies had a cavalry force of some 100,000 men, but the development of trench warfare rendered cavalry charges unviable as a military tactic. But horses and mules were still needed to transport materials and supplies and to pull guns and ambulances. The animals also had to be fed, watered and tended. Strong ties developed between horse and rider. The Daily Mail on 31st December 1914, carried an article by a Welsh soldier serving in the Royal Field Artillery. He’d been with his horses for several years before war broke out. He said;

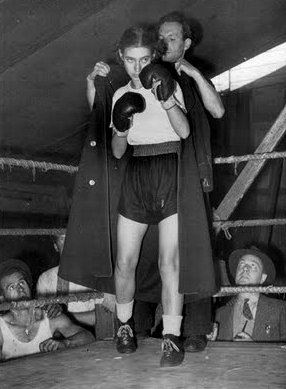

In February 1949, there were numerous press reports about “battling Barbara Buttrick”, a boxing typist from Hull who was due to fight Bert Saunders in an exhibition match at the Kilburn Empire. The bout was scheduled for March 7th, and she would become Britain’s first professional female boxer. But the fight was opposed by the Variety Artists Federation. Defiantly, Nat Tennens, the licensee of the Kilburn Empire said, “the show goes on”. Barbara’s promoter Micky Wood said, “There are women lion tamers, snake charmers, and trapeze artists. Why should this girl not box? She lives for boxing.”

In February 1949, there were numerous press reports about “battling Barbara Buttrick”, a boxing typist from Hull who was due to fight Bert Saunders in an exhibition match at the Kilburn Empire. The bout was scheduled for March 7th, and she would become Britain’s first professional female boxer. But the fight was opposed by the Variety Artists Federation. Defiantly, Nat Tennens, the licensee of the Kilburn Empire said, “the show goes on”. Barbara’s promoter Micky Wood said, “There are women lion tamers, snake charmers, and trapeze artists. Why should this girl not box? She lives for boxing.”