In 1929, Bernard Sheker was a 29-year-old clerk at a firm of paper makers in Holborn. He was ‘walking out’ with Hilda Lewis—a slim, pale girl. She was 19, and working as a typist for a firm near Finchley Road. Bernard had first made contact with Hilda about 18 months previously, when she telephoned orders from the printers.

Hilda told Bernard she was the daughter of a plumber, and had been adopted by a wealthy Indian tea planter named Cunningham. He had died two years ago, bequeathing her all his money on condition that she did not marry without the consent of her guardians or until she was 25. Hilda said she was a millionairess and showed Bernard photographs of her luxurious Green Street house in Mayfair. She also gave Bernard’s mother Rose expensive bouquets of flowers.

Later, Hilda said her guardians had died and an arrangement had been made for Lady Howard, the mother of the Duke of Norfolk, to chaperone her during the London season. The Shekers weren’t surprised when Hilda appeared in an evening gown, saying she had just slipped away from a smart party.

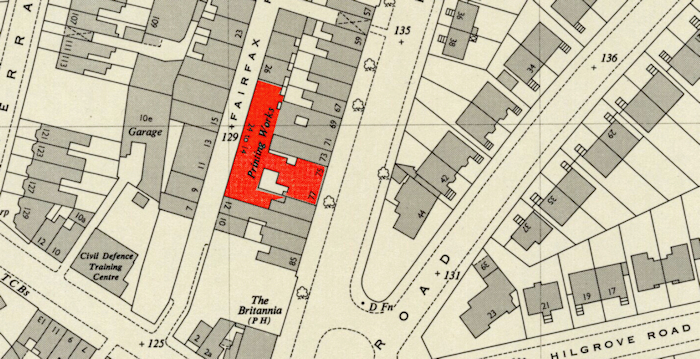

But if she had so much money, asked the family, why did she need to work? That was simply a way to pass the time, said Hilda, until she came into her fortune. She spent some of her time at a boarding house on Priory Road only to be close to her employers, the printers Baines and Scarsbrook at Nos.75-77 Fairfax Road.

Bernard, the eldest of four children, tried to persuade his parents that he should marry Hilda, even though she was not Jewish and ‘she was much above his station’. His father Aaron, who was deaf and dumb, was a ladies tailor, and the family lived at 70 Church Street in Stoke Newington.

Hilda wrote to Bernard about her society connections and explored the difficulties of their romance across class lines:

“We must stick it and get through: to part would be no remedy whatever. It would only bring more sadness and we would be wronging ourselves. I would still go on living, visiting, and entertaining and spending much money, but in reality I would be a beggar, just slipping through life and missing its real beauty.”

Instead, she saw a life where they were “perfectly united, sharing the same hopes and aims and desires, enjoying the same sunshine and weathering the same storms.” She ended the letter by saying, “I have a vision of happiness which fills me with joy.”

On 18 October 1929, Hilda took a major step towards realising her dream. That evening, she brought four cash boxes wrapped in brown paper to Bernard. She said she had lost the keys and asked him to force them open. He took the money and cashed some of the postal orders, a total of just over £138 – worth about £7,500 today.

The next day, Baines and Scarsbrook discovered their cash boxes were missing and Hilda and Bernard were arrested.

In March 1930, the jury at Marylebone Court believed Bernard’s story that Hilda had completely fooled him and his parents. He was discharged.

A trembling Hilda admitted stealing the safe key. She had hidden in the office until everyone had gone home and taken the cash boxes. Hilda was detained until the magistrates received a medical report on her. At the next session, Dr Morton, the governor and medical officer at Holloway, said Hilda’s letters contained extracts from several popular romantic novels by John Galsworthy, Muriel Hine and Marie Corelli. Morton said he had seen this kind of fantasy before and that Hilda was perfectly normal.

The chairman of the magistrates, Sir Robert Wallace KC, warned Hilda not to indulge her over-active imagination again and bound her over for 18 months probation on good behaviour.

When her love letters were read out in court the audience were convulsed with laughter. Writing for the Daily Mail, Beverley Nichols chided their reaction and pointed out that Hilda was physically and emotionally overwhelmed when she was forced to appear in the dock. Nichols had previously covered the sensational 1922 trial of Edith Thompson and her young lover Freddy Bywaters who had murdered Edith’s husband. This case had also demonstrated the dangers of fantasy and reading cheap fiction. Nichols asked his readers to have a “spark of imagination” and to empathise with Hilda. They should think of her writing to Bernard from her lonely room at Priory Road, imagining that stealing the money could provide a better life for them both.

Of course Hilda’s story was a complete fantasy. Ironically, she was the daughter of a police constable and had been born in 1910 at 30 Fleet Road, Hampstead. By the time of her trial, Hilda Lewis had worked for four years as a typist at Baines and Scarsbrook and her home was 42 Priory Road, a boarding house she shared with eight other women.

The court experience had clearly shocked Hilda. She stayed out of trouble and in 1941, she married Frederick Charles Maynard, a Kilburn man, and they lived at 25 Holmdale Road. What of Bernard? By 1939, he was living on Old Street and running a tobacconist and confectioner’s shop. His wife, Pauline, was a shorthand typist.