Housing targets 90 percent fulfilled with 14 years to go!

Last week we looked at job creation in West Hampstead. This week, we turn our attention to housing.

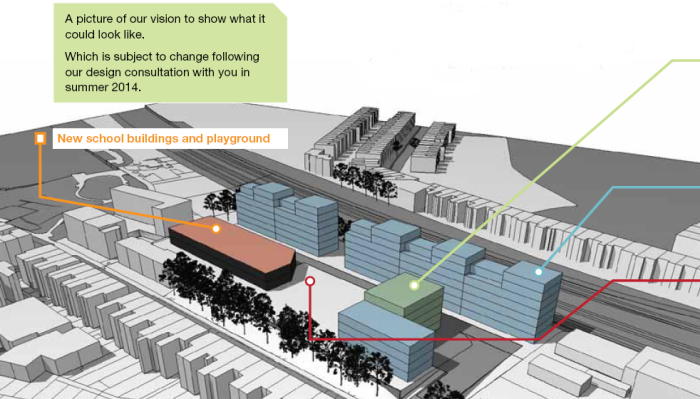

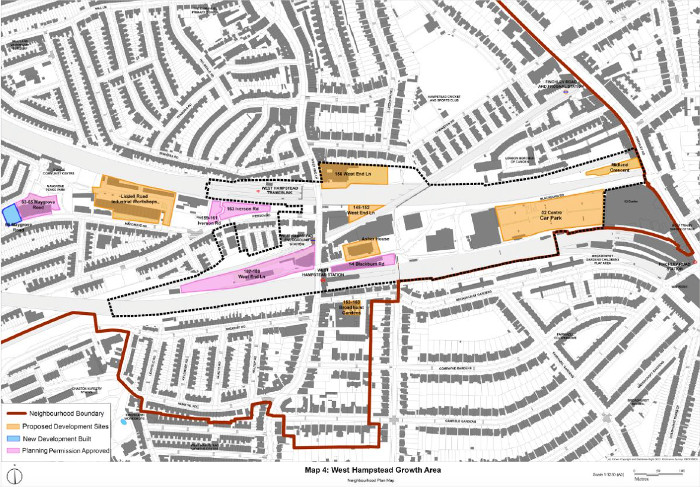

In the London Plan 2016, West Hampstead is glamorously referred to as “Area for intensification, number 45”. The original designation dates back to the time Ken Livingstone used to commute to City Hall via West Hampstead and no doubt saw all this space around the railway tracks. The “intensification” was to increase housing by 800 new homes and jobs by 100 in the Growth Area, mapped below.

In 2015, Camden confirmed these numbers in its own plan for the West Hampstead Interchange over the following 16 years, though this is substantially lower than the number outlined in its 2010 Core Strategy document, which was 2,000 new homes but was then scaled back to 1,000. The “Interchange” is almost exactly the same as the growth area.

It is not clear who originally drew the outline of the Growth Area, and why, for example, it didn’t include the council-owned light industrial site Liddell Road.

In early 2017, how is West Hampstead progressing towards this housing target?

Nido. The student housing on Blackburn Road immediately presents a challenge. It has 347 beds but unless you really stretch the definition of a “home”, that does not really equate to 347 new homes. A better measure, though not perfect, is to look at it as 39 shared-flats and 52 studios = 91 units.

Asher House. Next door to the student housing is the former Accurist offices, which was fairly quietly converted to residential under a government scheme to speed up planning that improved the valuation of the building without including any affordable housing. It was converted into 25 units, however, it is possible that it may be fully redeveloped in the future, which would be likely to add a couple of stories.

West Hampstead Square. If anyone ever actually moves in, then its seven blocks contain 198 units (145 market, 33 affordable rented, 20 shared ownership).

156 West Lane. The Travis Perkins building that’s just been given the go-ahead for redevelopment will have 164 units (85 market, 44 affordable rent, 35 shared ownership).

And 198 new flats at West Hampstead Square

That’s 478 units so far within the Growth Area, but there are a number of large developments that fall just outside the Growth Area, but at the same sort of density. Should they be included in the targets? We are talking about large-scale dense developments on the fringes of the growth area and whose residents will certainly be gravitating to West Hampstead for their transport needs in particular.

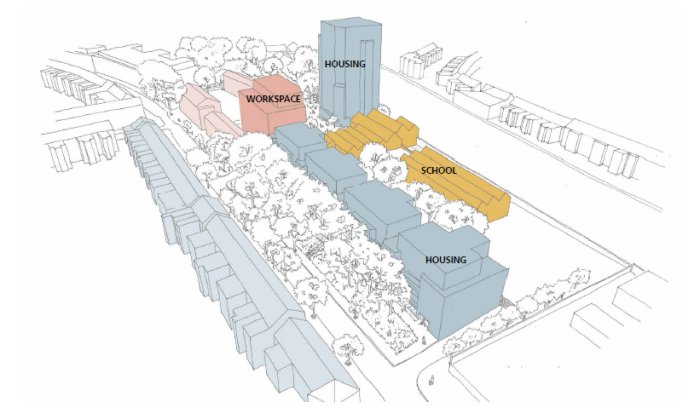

Liddell Road. The largest of these developments, Liddell Road includes 106 units of housing to sit alongside the school (indeed, paying for the school). Just four of these units will be at affordable rents.

The Residence. Next door at 65-67 Maygrove Road, this scheme includes 91 units (79 market, 4 shared ownership, 3 social rented and 5 affordable rented).

The Ivery & The Central. The old Iverson Tyres site has 19 units (15 market, 2 shared ownership, 2 social rented) while the former garden centre site next door has 33 units (23 market, 7 socially rented, 3 shared ownership).

Adding these additional 249 to the 478 gives us 727 housing units – 90% of the housing target for 2031!

There are at least three other sites in the planning pipeline, although progress is slow and final numbers speculative.

11 Blackburn Road. This attractive but run-down Victorian warehouse had a planning application for six 2-bed houses and the conversion of the main warehouse into B1 employment space downstairs with a couple of flats upstairs. Nothing seems to be happening with this at the moment, but there’s a potential 8 units.

14 Blackburn Road. Way back in 2004, permission was granted to redevelop the Builders Depot. This was for two 4-storey blocks, one with employment space and one with 8 houses and 6 flats, plus underground parking. This permission has now lapsed so would have to be renegotiated, but these 14 units, would likely be the minimum of any new proposal.

Finally, Midland Crescent. That’s next to the O2 centre on the Finchley Road – which still counts as the West Hampstead Growth Area. This has been refused planning permission three times. The latest proposal included student housing, private housing, a shop and employment space. Again any estimate of potential is speculative, but the latest application would have delivered 40 units.

That’s a potential extra 62 new units within the growth area, but on top of that there are other sites that could be – and in some cases will be – redeveloped for housing: The Taveners Yard on Iverson Road, the Paramount carpark and – the big one – the O2 carpark.

At the workshop on the 02 carpark, there was talk of 300 new homes as well as employment and retail space. In one fell swoop West Hampstead could soar past the 1,000 new homes target. Maybe then, the tube station would finally be decreed worthy of an upgrade. Maybe.