Judgement day approaches for 156 West End Lane

The proposals for 156 West End Lane (aka Travis Perkins) roll on. Two(?), three(?) years after it was first announced, are we into the final stretch? The latest planning application has opened for comments and the deadline is 10th November.

To recap

The development is for 164 flats of which 79 are affordable (44 social rented and 35 shared ownership) and 85 are for private sale. Although less than half the flats are “affordable”, they are on average larger and thus 50% of the floorspace is deemed “affordable” (which is how the quota works). The proposal also includes 1,919m2 of employment space; 763m2 retail space, 500m2 of ‘start-up space, 63m2 of community space and 593m2 of office space.

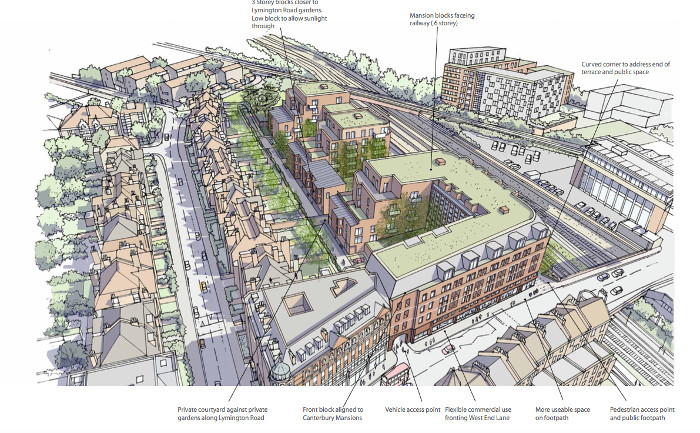

156 West End Lane latest plans. Image via Design and Access Statement

There are copies of the latest summary of the proposals on Camden’s planning website and at the library, though the easiest way to read it is on developer’s A2Dominion website. Unfortunately, this latest summary focuses on the changes made to previous proposals, but doesn’t recap some basic issues. To understand the last round of plans, our July article may help.

Why a new proposal? The original application was submitted last November, but was put on hold because both Camden’s planning officer and the GLA (Greater London Authority) had concerns. Developer A2D has since tweaked (‘improved’) the plans and thus submitted a new application for consultation.

Three local groups have studied the application in depth. The Neighbourhood Development Forum and Stop the Blocks both oppose the proposal (click the links to read their submissions, although these relate to the original proposal. Doubtless they will comment again). WHAT, the third local amenity group, is becoming less active and has focussed its efforts on ensuring that affordable rents really are affordable (it seems they will be set at 40% of market rents). As you have may have read in the CNJ’s letter pages and on its own website, Stop the Blocks is critical of the other two groups’ approach to the scheme.

More background information, as if wasn’t complicated enough already, is that the site is part of the West Hampstead ‘Growth Area’. This means that it is deemed capable of large scale development, primarily housing. However, the site is also adjacent to a conservation area, which any development is supposed to take into account.

How big is too big?

The single biggest issue with the proposed development is its scale. The original sales brochure for the site sums it up neatly: “The site offers the greatest potential for higher scaled development to the western frontage [West End Lane] and to the south towards the railway lines, with a transition in scale towards the more sensitive residential interface to the north [Lymington Road]”.

In other words, it’s a big plot of land that the agents felt could take a large building. It’s worth remembering that in a local survey a few years ago, the existing building was the second most unpopular in West Hampstead – a failed attempt by Camden in the 1970s to build an iconic building.

As it stands, the proposed building occupies the full frontage along West End Lane at six storeys (but the top one set back), reducing in height as it moves back from West End Lane along the railway tracks. Following the initial consultation, A2D has reduced the visual impact on West End Lane, arguing that the new design fits better with the adjacent Canterbury Mansions, although the corner tower in the final proposal looks a bit odd and is visually jarring.

A 3D view from a slightly earlier scheme as A2D hasn’t supplied a new one. Main difference is that east building is now one storey lower.

In the latest proposal, the developers have lowered the height of the east building by one storey to help reduce the impact from Crediton Hill and the conservation area. These are slight improvements from the first proposal, but at least one person with local experience of assessing these applications still feels the development is too ‘blocky’ along the railway tracks. Will the reduction by one floor be enough to appease the critics?

The new proposals (left) show the far eastern end is one-storey lower than the original plans (right)

One way to judge whether the proposals are too dense is to benchmark the scheme against the London Plan’s guidelines. This considers the type of neighbourhood (West Hampstead qualifies as ‘urban’) and level of public transport (‘very good’). These criteria suggest a maximum density of 700 habitable rooms per hectare and up to 260 units per hectare. The current plans for 156 West End Lane have 786 habitable rooms and 288 units per hectare, suggesting that the development may be too dense.

Where did the sun go?

There is a “right to light” in planning law that often comes into play when tall buildings are being planned. In the earlier application, Stop the Blocks picked up on some discrepencies in the sunlight reports and were concerned that the outdoor games area would be overshadowed. Camden asked A2D to clarify: A2D’s consultants, John Rowan and Partners, maintain that sufficient light would still reach the buildings on Lymington Road after redevelopment. Different consultants ‘Right to Light’ Surveyors, asked specifically about the multi-use games area (MUGA), agree that although there would be increased shadows, the impact would be acceptable.

There is also an independent assessment by Anstey Horne which states both that “we consider that the overall level of adherence is good and where there are reductions beyond the BRE guidelines, the retained levels of daylight and sunlight are in-keeping for an urban setting“. And for the MUGA that “although there is some overshadowing in the afternoon by the proposed development, the MUGA area will meet/exceed the BRE guideline recommendations for sunlight availability“.

The jobs equation

Camden’s policies appear ambiguous on the issue of employment space. On the one hand the council wants to protect employment space and developments need to provide an equivalent amount of employment space to any that would be lost. On the other hand, the council wants to prioritise housing. As happened at Liddell Road, where the industrial estate was wiped out for a new school, flats and some office space, the idea of “equivalence” is vague. Camden does generally seem to be stricter with private developers (e.g., forcing the Iverson Tyres site to keep light industrial space, which has only now just been reclassified as office space after no tenants appeared), but more flexible when redeveloping its own sites.

Currently there is 4,019m2 of employment space on site; the former council office space of 2,401m2 and retail showroom/builders merchants of 1,618m2. This will be replaced by 1,919m2 of employment space; 763m2 retail space, 500m2 of ‘start-up space, 63m2 community space and 593m2 office space.

Travis Perkins (TP), the existing employer on site, is arguing strongly that it should be allowed to remain. However, it is only a leaseholder from Camden, which has now given it notice, so it’s not clear on what legal grounds TP could insist on staying. TP also had the option to purchase the site and redevelop it themselves, but chose not to.

There’s also some disagreement about what constitutes employment space. Camden argues that the Wickes showroom, the TP shop, and the old council offices all constitute employment space; TP wants to include the whole yard area, which would mean the current proposal falls short of maintaining the same employment space.

TP has pointed out that when it redeveloped its yard at Euston (which now has student housing on top) Camden insisted TP retained the same amount of employment space; but now Camden is redeveloping its own site it is allowing/arguing for more flexibility. Funny that.

The thorny affordable housing question

Camden required A2Dominion to ensure that 50% of the housing area was for ‘affordable’ units. We have discussed the issue of what “affordable” means before. From a developer’s perspective, A2D has to make the numbers add up. It has to pay Camden a reported £25 million for the site, build 50% affordable housing that is less profitable, and still make a normal development profit.

Overall, 79 of the 164 units are designated “affordable”: 44 social rented (at a to-be-confirmed 40% of market rent) and 35 shared ownership. Whether shared ownership truly constitutes affordable housing is another debate.

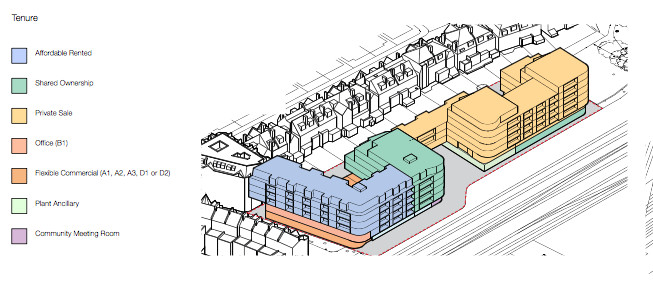

Different types of ownership proposed for 156 West End Lane. Source: Design and Access Statement

What does it mean for West End Lane?

Sometimes, a focus on design and other issues can be at the expense of practicalities, for example the Sager building (Alfred Court) by Fortune Green was approved with an internal courtyard for commercial deliveries— but the entrance is too low for delivery trucks to enter. Yes really!

Deliveries could be an issue for 156 West End Lane too. The original plans claimed that the proposal met Department of Transport delivery criteria and would allow refuse collection and ‘small’ articulated lorries to back into the internal loading bay, but it seems tight. If, as with Alfred Court, it turns out to be impossible, then lorries would park on West End Lane and we’d have an escalation of the problems caused by Tesco lorries and more traffic chaos on West End Lane. No thank you.

As we discovered with Tesco, once deliveries start, it is nigh impossible to change them, so it is really important that this addressed at the planning approval stage and not left to be finalised later. There is also the practicalities of vehicles crossing the pavement onto West End Lane.

A serious issue hanging over 156 West End Lane is the size of the retail units. The focus on TP and employment space has led to less scrutiny of what the new commercial space will actually be. One reason the current building is so unpopular is that it is ‘dead’ frontage on West End Lane. To be successful it needs to be ‘active’ frontage, but another large unit on the scale of Wickes would not be much better.

Dull frontage on West End Lane – new development can, and must – do better than this.

Of course, planning has little control over this; it can specify only that the space should be retail, it cannot dictate the size of the units. The latest plans propose a flexible retail space potentially up to 678m2. That’s supermarket size. Yet would replacing the current frontage, which is rather dull compared to the variety on the rest of West End Lane, with another uniform frontage be any improvement? Even the option of three retail units would still see three sizeable units, but this is perhaps the least worse option.

A2D has promised that as site owners, it will be a good neighbour. Yet it is probably in its financial interest to lease the retail space as one site. With three —soon to be four—supermarkets on West End Lane, does West Hampstead really need another one?

What is the impact on local amenity?

What even is “amenity”? In this case it’s both the useful facilities of a building and the impact on the “pleasantness” of an area. The proposed development will affect amenity in both good and bad ways.

Firstly, your personal taste will dictate whether you think the building itself will enhance the area. Few would argue that it is replacing an unloved building. But as we’ve seen, the impact on views and sunlight is more contentious.

The development will create a new public open space and improve the rundown Potteries path, both positive impacts. A2D is also building a new community room, though it is not clear who will bear the cost of managing it.

Finally, A2D will be required to pay CIL (the community infrastructure levy that replaces the old Section 106 money) although it is not clear exactly how much it will have to pay but the most likely scenario is that it will have to pay £250 per m2 on the 7,657m2 of market housing, which comes to £1.9 million (25% of which stays in the area) plus £25 per m2 of the commercial space. This would allow improvements to other local facilities though tracking how this money is spent is a whole other issue.

Conclusion

The plans for 156 West End Lane show, yet again, that the planning system doesn’t work effectively. London is desperately short of housing and this scheme provides both private and social housing. It is being put forward by a housing association (which is using private development profits to build more social housing). And all that seems to have got lost.

No wonder; go to Camden’s planning portal and there are now more than 400 relevant documents online for this one plan. It’s overwhelming and nigh on impossible to get a handle on them all. This is not to say that the proposals are bad, just that it’s extremely difficult to judge them in an objective way. In fact, the latest plans are an improvement on the original versions – the design is better and they are quite a bit lower. A cynic might wonder whether A2D chose to start off with the worst-case scenario and then be seen to reflect local feedback to end up with what it had in mind all along.

The situation is complicated further by the fact that the fate of this Camden-owned site will be judged by… Camden councillors. Camden’s planners do seem to have influence on the proposal – their reservations (along with those of the GLA), were why the scheme was put on ice last year. Nevertheless, there is an annoying – if understandable – lack of transparency on their discussions so we don’t know exactly what issues concerned them. Once the planning officer reaches his decision – which will be a recommendation to approve or not approve, the decision goes to a vote. Given Labour’s dominance in Camden, and this redevelopment helping fund the new council offices at Kings Cross, there seems little doubt that if the recommendation is to approve, the same verdict will follow.

There is one significant issue that could derail it. The issue of employment space that we set out above is being challenged by deep-pocketed Travis Perkins. It’s a technical planning issue, and not top of the list of local concerns, but it could still have an influence as a legal technicality.

West Hampstead is having to cope with a lot of new development, and 156 will add to that; but are we getting our fair share of the benefits? Camden’s other growth areas – which it needs to meet its housing targets – have had money spent on masterplanning, but West Hampstead has not. This means that there are a series of disjointed developments that lack coherence.

There are significant errors in this article Mark not least is the claim that the development reduces in height. In fact it is the opposite with seven storey blocks towards the south and east. This contravenes Camden’s Site Allocation document which requests transition in massing and height towards the south and east. The developer deceitfully claims that: “a higher degree of obstruction maybe unavoidable if new developments are to match the height and proportions of existing buildings. We note that the proposed development is to be of a similar height and proportion to that of the existing surrounding buildings. In particular, we note that the proposal seeks to match the height and proportions of the adjacent property at 166-174 West End Lane.”

On the employment floor space you have made the same error as the developer’s in failing to include the current builder’s yard in your figures.

Regarding the deeply flawed sunlight/daylight assessment we continue to await a further analysis of the methodology and modelling for the Daylight/Sunlight report which Anstey Horne will be conducting after the developer provides the information requested by Camden planners.

It was with some amusement that we read the developer’s excuse for significant discrepancies between the ‘before development’ figures published in the November and June daylight/sunlight reports. John Rowan & Partners claimed:

“There are a number of differences between the November 2015 and the June 2016 reports, mainly as a result of additional survey information becoming available and changes to the proposed design which resulted in an overall reduction to the massing. In respect of windows 302 to 304 (new report numbering) increases to the height of the existing boundary wall (and fences) were made based on the additional information shown on the architect’s drawings. The wall is higher than our previous estimations and this resulted in a reduction in both the before and after results. The proposed design had also been reduced in size by the time of the June 2016 report which led to the before and after results being closer together, thereby resulting in a higher before/after ratio.”

The garden walls are 7 foot high at the end of 14+ metre gardens and cannot possibly interfere with the daylight/sunlight to windows before development. There is also no significant or noticeable reduction in height nor bulk of the proposal, only the removal of a section of the seventh storey block on the eastern end to be replaced with a private sun-drenched roof garden.

We have asked and will continue to ask that the consultation period be extended whenever material is released by the developer and, further, when the Anstey Horne report is published.

We will continue to campaign for Camden to commission a fully independent daylight and sunlight study to be conducted on the basis that we have demonstrated concerning discrepancies in the figures published so far, to the extent that no faith can be placed in either set of figures provided and, additionally, that the developer has consistently withheld technical information and 3D modelling diagrams that would allow Camden planners and local residents alike to determine the true impact of the proposal.

Dear Save West Hampstead,

Thank you for your comment on this important West Hampstead issue. I tried to stay relatively neutral (and concise) on it so that our readers get the facts to decide for themselves, but things might not have been 100% clear. You raised the following three points:

The development does drop away a little to the east (recently, to reduce the impact from Crediton Hill) and more to the north. Whether this is enough or not is a central question for the application. As I raised in the article ‘how big is too big?’ and we expressed concerns about the blockyness of it. Since it is complicated to understand we have added images of earlier drawings of the East building along side the current proposal in the article.

As for including the yard as employment space although it wasn’t in my figures I stated that Travis Perkins wanted to include it whole and with their deep pockets they might prevail on that point.

Finally, it is not clear if Anstey Horne, who have already done a summary report on the sunlight will do another one, and if it will make any material difference. If new evidence comes ‘to light’ (excuse the pun) we will report in more detail on this.

Can you please be accurate if you are truly attempting to be factual – the eastern block is seven storeys with a roof garden (presumably with a wall of approx. half a storey) replacing a small proportion of the far eastern end. To go from six to seven storeys requires an increase in height. You claimed: “As it stands, the proposed building occupies the full frontage along West End Lane at six storeys (but the top one set back), reducing in height as it moves back from West End Lane along the railway tracks.”

The builder’s yard does require inclusion in the employment space figures and has nothing to do with deep pockets.

Yes Anstey Horne have been requested to carry out further investigation of the modelling and methodology by Camden which we have insisted on, as their first report stated: “We have not interrogated any of the technical analysis produced by Rights of Light Consulting and have assumed they have modelled the adjacent properties adequately from survey information and research, as well as interpreting the existing and proposed drawings for the massing on the development site. Ideally Rights of Light Consulting would have produced some 3D views of the existing and proposed conditions, so that some sort of visual comparison could be made to the planning drawings, but they have not shown any modelling information.”

Camden responded to our disbelief at these assumptions with: “Understood re modelling. As a result of the AH report we’ve requested their technical modelling analysis which we will have checked by AH. I’ve also asked the applicant to respond to your dossiers of Lymington Road properties.”

We have yet to receive any of the above.

As for quoting Camden’s Site Allocation Document we suggest this is more appropriate in regards to the proposal: “If redeveloped, the existing relationship of new development immediately adjoining Canterbury Mansions to the north should be considerably more sympathetic in terms of scale, height and design with an appropriate transition in massing towards the south and east of the site.”

We assume you have a large readership Mark and it should not require us to correct what are significant but telling errors amounting to misinformation within your article especially on such an important development and one which resident’s have shown much anger and dismay about. We look forward to reading an amended article with accurate and factual information for your readers.

I think the issue seems to be “height” vs “roofline”. Because the land slopes down to the east, a taller building can have the same roofline or elevation as a shorter building to the west. This is very clear from the illustration. So having removed a storey from the eastern end of the eastern block, the development does indeed drop in elevation because the eastern end is at a lower elevation than the western end. The effect therefore for anyone looking at the development from across the railway tracks would be that it reduces in height as it goes from west to east. The far east side is taller than the far west side, but also lower.

I’m not clear, therefore, what the “significant” errors are in this piece? Mark’s already explained that the article points out that there is disagreement on whether the builder’s yard should or shouldn’t be included as employment space in this context – some think it should, others clearly think it shouldn’t.

Your extra information about the sunlight surveys is very interesting. We shall be keen to find out the outcome if/when the right models are produced. Your detail certainly adds to what Mark wrote, though does not contradict it – so I don’t see any error here.

Perhaps rather than bandying around accusations of factual inaccuracies, you could be very specific as to what they are. I’m sure that if Mark has inadvertently made a mistake he will be only too glad to rectify it.

Only if you look at the development from one angle which is the one presented here. Lymington Road as does West End Lane also slopes but does this reduce the height? It isn’t being built in a hole!

No errors? How about this:

A 3D view from a slightly earlier scheme as A2D hasn’t supplied a new one. Main difference is that east building is now one storey lower.

No it isn’t it remains seven storeys with a reduction of approx. half a storey to accommodate a sun-drenched roof garden for those who will be able to afford these flats at the eastern end.

And again: Will the reduction by one floor be enough to appease the critics?

How about this? ” Stop the Blocks picked up on some discrepancies in the sunlight reports and were concerned that the outdoor games area would be overshadowed.” Not true as we are extremely concerned with the impact on the valuable and protected Open Space at Crown Close which we have shown will be plunged into shadow by these block during evenings when most used after school. This space is protected by policies from the NPPF down to the NDP. That the light and sunshine stolen from local children and families is proposed to light up the private block’s roof garden is a gross and contemptible injustice.

We could go on and on picking out the factual errors which we have already made you aware of. Perhaps you could check your facts before publishing instead?

These are not factual errors. These are areas where you disagree with how Mark presented the information.

The eastern side of the building IS one storey lower than it was in the original plans. It’s clear from the illustration. Whether there’s a roof garden or not (and whether it’s got access to better weather than the rest of the UK) is not the point. The building has been reduced by one storey at the eastern end.

And you’re saying that it’s factually incorrect to say that you found discrepancies in the sunlight reports and were concerned about overshadowing of the games area? You have obviously said a lot more about many things, and we have linked to your site so people can see that. But are you suggesting that you’re not concerned about the overshadowing of the games area, or that you didn’t question the sunlight reports? If so, that sentence can easily be removed completely.

You say you could go on and on picking out the factual errors you have already made us aware of. You have yet to make us aware of a single one.

“Given Labour’s dominance in Camden, and this redevelopment being part of Labour’s much vaunted capital investment programme” Not true the receipt from the sale of the land is simply to pay for the new offices at 5Pancras Sq which replaces ALL local provision not just 156 WEL. CIP it is not.

Apologies if this is out of date – from Camden council: “The District Housing Office at 156 West End Lane is a key site within the town centre, with various council office functions on West End Lane and Travis Perkins builders’ merchants to the rear. The decision has been made to dispose of the site to generate funds for investment in CIP priorities like

community centres, schools and housing estates.”

if you have evidence of something more recent that proves your assertion above, then I’m sure Mark will be happy to amend the article accordingly.

Camden undertook a ‘consultation’ after deciding to sell the Town Hall extension. The consultation document contained the following information, with 156 West End Lane languishing at the bottom of the asset ‘disposal’ list:

———————————————————–

It would cost £20m to refurbish the Town Hall extension, plus substantial rental and running costs associated with temporarily relocating staff and service off-site. This would mean finding additional budget, which is simply not available in this financial climate and would have had to come from further cuts to service budgets or increasing rates — something we are not prepared to do.

We need to take a different approach which means that we are selling:

– Bidborough House

– Cockpit Yard

– Crowndale Centre (the library to be re-provided)

– Jamestown Road

– Roy Shaw Centre / Cressy Road

– Town Hall extension

– 98-100 St Pancras Way

– 156 West End Lane

We have or will end leases at Bedford House, Clifton House and 42 Caversham Road.

The Town Hall will not be sold, it will be retained to continue council services.

The new building at Pancras Square is due to be ready by summer 2014. The Town Hall extension sale will not be completed until services have moved into the new building.

———————————————————–

Source for the above text: https://consultations.wearecamden.org/culture-environment/consultation-on-town-hall-extension-your-role-in/user_uploads/town-hall-extension-consultation-slidepack.ppt

———————————————————–

So, as shown, any receipt from 156 West End Lane was earmarked to pay for the new council offices at Pancras Square, which is not quite the same as “CIP priorities like community centres, schools and housing estates”.

Alternatively, a Camden press release states the following:

“The sale or termination of leases at seven existing buildings will pay for the new [council office] building and means the Council can create new facilities for the community at no additional cost to taxpayers.”

Source: Camden Council: Camden signs deal for Three Pancras Square at King’s Cross

http://camden.gov.uk/theme/camden-bremen/ccm/content/press/2011/august/camden-signs-deal-for-three-pancras-square-at-kings-cross/

CIP takes place on “sites we [Camden] own”.

156 West End Lane is part of a Council “disposal” programme, not CIP, as the site would no longer be owned by Camden Council.

Thanks for the update. We’ll amend. We obviously weren’t suggesting that 156 was a beneficiary of the CIP, but we clearly missed that the sale was now funding the new council offices.

Look forward to seeing the update.

The sale of 156 West End Lane was only ever intended to fund the new council offices.

All of this was included in the Save West Hampstead “Stop the Blocks!” objections document submitted in response to the original planning application.

For anyone that hasn’t read it there’s a copy here:

https://savewesthampstead.wordpress.com/planning-issues/save-west-hampstead-stop-the-blocks-objections-to-planning-application-20156455p/

As the scheme hasn’t been significantly modified to address any of the concerns raised, the objections outlined therein still stand.

Duly updated to reflect the CIP information.

Perhaps now you’d be kind enough to make your own corrections to those comments that accuse us of “significant errors”, “significant but telling errors”, being “misleading”, etc. It seems that rather than there being “significant but telling errors”, there was actually one entirely accidental error based on out-of-date information (which rather belies your point that the sale was “only ever intended to fund the new council offices”) about where Camden was spending the money from 156.

Could Mark kindly explain why the only reference to “open space” is in a paragraph about the proposed development?

While the “outdoor games area” would be overshadowed by the proposed development, so too would the Designated Open Space in Crown Close.

It is a curious fact — no doubt a coincidence — that this article by the former Treasurer of the NDF, the NDF itself, and the developer behind the 156WEL scheme have all chosen to focus their attentions on the Multi Use Games Area, while neglecting to make explicit reference to the Designated Open Space which is afforded protection at all levels of the planning hierarchy.

Oh of course… i knew it MUST BE A CONSPIRACY. Groan. Is everyone who doesn’t share your precise point of view in on it? Or just those who stick their head above the parapet?

The comment to which you replied made reference to a “coincidence”, you chose to use the word “conspiracy”.

That the Designated Open Space has protections throughout the tiers of planning policy hierarchy is not merely a “precise point of view”, it’s a fact.

That the author of the article, the NDF and the developer have all opted to ignore this fact of planning policy is also a fact.

https://uploads.disquscdn.com/images/d768741f1f8b8ccb4ae3e2cb82f7bda0abe85c708a39f0b6ef1d60c526988e7f.png

That “Lorries would park on West End Lane and we’d have an escalation of the problems caused by Tesco lorries and more traffic chaos on West End Lane. No thank you.” is already part of the proposed “Waste Management Strategy”.

And it’s for the occupants of start-up units and the so-called community room to sort out their own refuse collections, not A2Dominion as the wannabe owners and managers of the site.

Quoting from the Waste Management Strategy document submitted with the application:

“The start-up units and community meeting room will each have internal waste storage and will arrange for their own waste collections directly from their units. Commercial waste collection vehicles would stop temporarily on West End Lane and waste would be manually transferred from the units back to the awaiting vehicle.”

The “more traffic chaos on West End Lane. No thank you” scenario has been designed into the scheme from its inception.

https://uploads.disquscdn.com/images/9581c266dc09718e6169452f9b1cfd8fbd959643cee2231c6ca952468cb5bd8e.png

The “traffic chaos” explicitly referred to deliveries not waste collection. Surely the waste collection situation would most likely be that the existing waste collection lorry that already serves West End Lane businesses would also stop at 156, so other than the additional brief stop, it wouldn’t make much difference to traffic. If deliveries throughout the day had to stop on the road however, when today they can go into the builders yard, the impact would be greater.