The proposals for 156 West End Lane (aka Travis Perkins) roll on. Two(?), three(?) years after it was first announced, are we into the final stretch? The latest planning application has opened for comments and the deadline is 10th November.

To recap

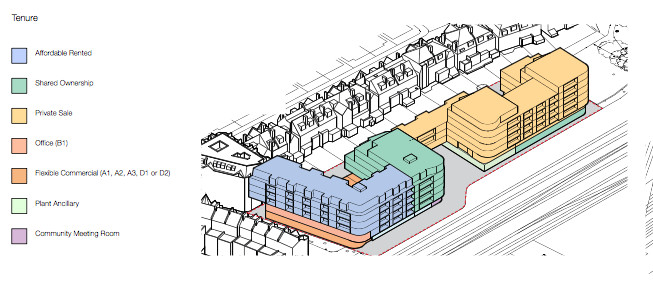

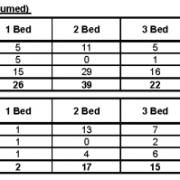

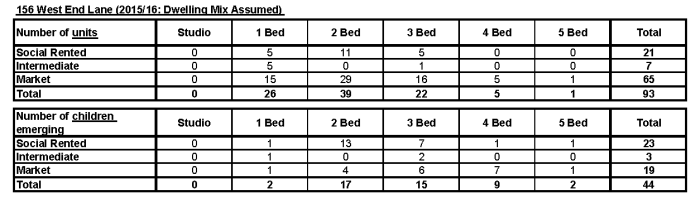

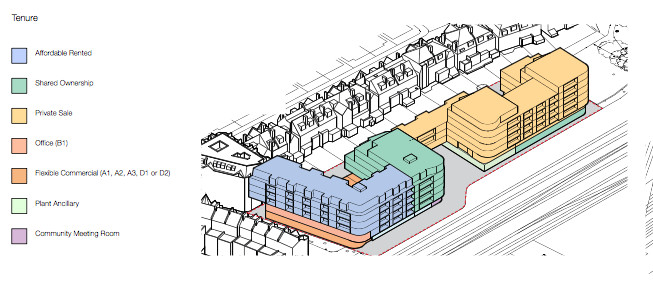

The development is for 164 flats of which 79 are affordable (44 social rented and 35 shared ownership) and 85 are for private sale. Although less than half the flats are “affordable”, they are on average larger and thus 50% of the floorspace is deemed “affordable” (which is how the quota works). The proposal also includes 1,919m2 of employment space; 763m2 retail space, 500m2 of ‘start-up space, 63m2 of community space and 593m2 of office space.

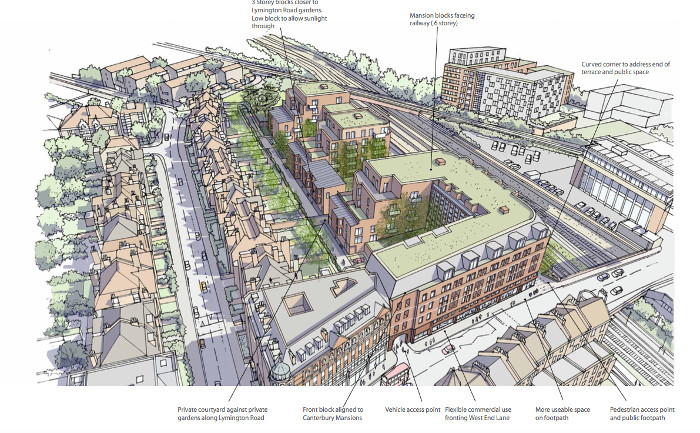

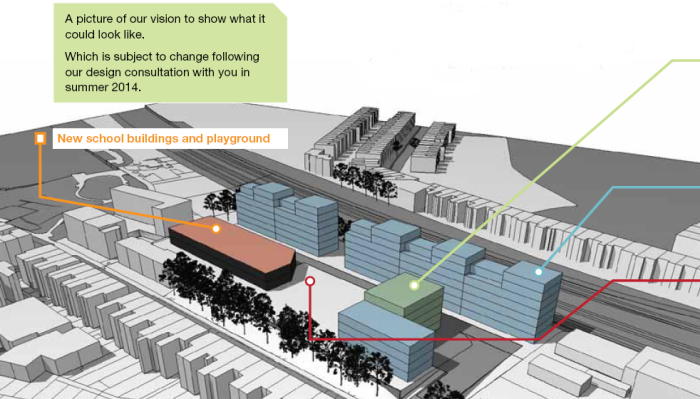

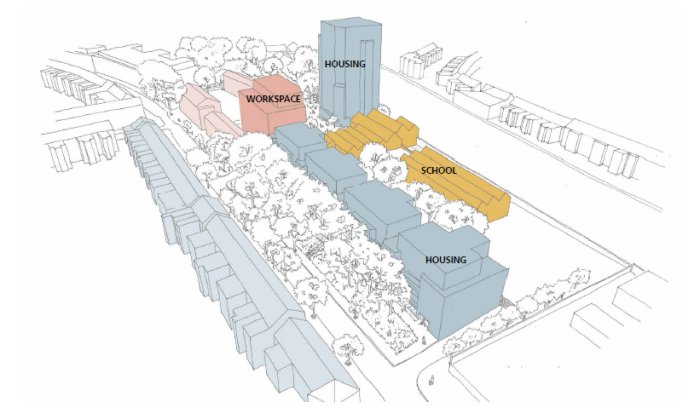

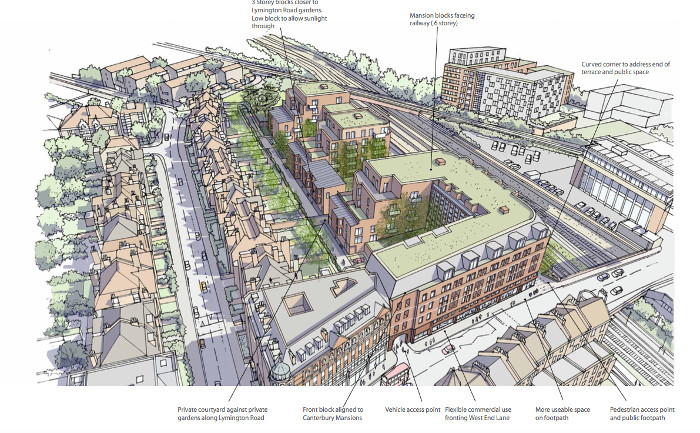

156 West End Lane latest plans. Image via Design and Access Statement

There are copies of the latest summary of the proposals on Camden’s planning website and at the library, though the easiest way to read it is on developer’s A2Dominion website. Unfortunately, this latest summary focuses on the changes made to previous proposals, but doesn’t recap some basic issues. To understand the last round of plans, our July article may help.

Why a new proposal? The original application was submitted last November, but was put on hold because both Camden’s planning officer and the GLA (Greater London Authority) had concerns. Developer A2D has since tweaked (‘improved’) the plans and thus submitted a new application for consultation.

Three local groups have studied the application in depth. The Neighbourhood Development Forum and Stop the Blocks both oppose the proposal (click the links to read their submissions, although these relate to the original proposal. Doubtless they will comment again). WHAT, the third local amenity group, is becoming less active and has focussed its efforts on ensuring that affordable rents really are affordable (it seems they will be set at 40% of market rents). As you have may have read in the CNJ’s letter pages and on its own website, Stop the Blocks is critical of the other two groups’ approach to the scheme.

More background information, as if wasn’t complicated enough already, is that the site is part of the West Hampstead ‘Growth Area’. This means that it is deemed capable of large scale development, primarily housing. However, the site is also adjacent to a conservation area, which any development is supposed to take into account.

How big is too big?

The single biggest issue with the proposed development is its scale. The original sales brochure for the site sums it up neatly: “The site offers the greatest potential for higher scaled development to the western frontage [West End Lane] and to the south towards the railway lines, with a transition in scale towards the more sensitive residential interface to the north [Lymington Road]”.

In other words, it’s a big plot of land that the agents felt could take a large building. It’s worth remembering that in a local survey a few years ago, the existing building was the second most unpopular in West Hampstead – a failed attempt by Camden in the 1970s to build an iconic building.

As it stands, the proposed building occupies the full frontage along West End Lane at six storeys (but the top one set back), reducing in height as it moves back from West End Lane along the railway tracks. Following the initial consultation, A2D has reduced the visual impact on West End Lane, arguing that the new design fits better with the adjacent Canterbury Mansions, although the corner tower in the final proposal looks a bit odd and is visually jarring.

A 3D view from a slightly earlier scheme as A2D hasn’t supplied a new one. Main difference is that east building is now one storey lower.

In the latest proposal, the developers have lowered the height of the east building by one storey to help reduce the impact from Crediton Hill and the conservation area. These are slight improvements from the first proposal, but at least one person with local experience of assessing these applications still feels the development is too ‘blocky’ along the railway tracks. Will the reduction by one floor be enough to appease the critics?

The new proposals (left) show the far eastern end is one-storey lower than the original plans (right)

One way to judge whether the proposals are too dense is to benchmark the scheme against the London Plan’s guidelines. This considers the type of neighbourhood (West Hampstead qualifies as ‘urban’) and level of public transport (‘very good’). These criteria suggest a maximum density of 700 habitable rooms per hectare and up to 260 units per hectare. The current plans for 156 West End Lane have 786 habitable rooms and 288 units per hectare, suggesting that the development may be too dense.

Where did the sun go?

There is a “right to light” in planning law that often comes into play when tall buildings are being planned. In the earlier application, Stop the Blocks picked up on some discrepencies in the sunlight reports and were concerned that the outdoor games area would be overshadowed. Camden asked A2D to clarify: A2D’s consultants, John Rowan and Partners, maintain that sufficient light would still reach the buildings on Lymington Road after redevelopment. Different consultants ‘Right to Light’ Surveyors, asked specifically about the multi-use games area (MUGA), agree that although there would be increased shadows, the impact would be acceptable.

There is also an independent assessment by Anstey Horne which states both that “we consider that the overall level of adherence is good and where there are reductions beyond the BRE guidelines, the retained levels of daylight and sunlight are in-keeping for an urban setting“. And for the MUGA that “although there is some overshadowing in the afternoon by the proposed development, the MUGA area will meet/exceed the BRE guideline recommendations for sunlight availability“.

The jobs equation

Camden’s policies appear ambiguous on the issue of employment space. On the one hand the council wants to protect employment space and developments need to provide an equivalent amount of employment space to any that would be lost. On the other hand, the council wants to prioritise housing. As happened at Liddell Road, where the industrial estate was wiped out for a new school, flats and some office space, the idea of “equivalence” is vague. Camden does generally seem to be stricter with private developers (e.g., forcing the Iverson Tyres site to keep light industrial space, which has only now just been reclassified as office space after no tenants appeared), but more flexible when redeveloping its own sites.

Currently there is 4,019m2 of employment space on site; the former council office space of 2,401m2 and retail showroom/builders merchants of 1,618m2. This will be replaced by 1,919m2 of employment space; 763m2 retail space, 500m2 of ‘start-up space, 63m2 community space and 593m2 office space.

Travis Perkins (TP), the existing employer on site, is arguing strongly that it should be allowed to remain. However, it is only a leaseholder from Camden, which has now given it notice, so it’s not clear on what legal grounds TP could insist on staying. TP also had the option to purchase the site and redevelop it themselves, but chose not to.

There’s also some disagreement about what constitutes employment space. Camden argues that the Wickes showroom, the TP shop, and the old council offices all constitute employment space; TP wants to include the whole yard area, which would mean the current proposal falls short of maintaining the same employment space.

TP has pointed out that when it redeveloped its yard at Euston (which now has student housing on top) Camden insisted TP retained the same amount of employment space; but now Camden is redeveloping its own site it is allowing/arguing for more flexibility. Funny that.

The thorny affordable housing question

Camden required A2Dominion to ensure that 50% of the housing area was for ‘affordable’ units. We have discussed the issue of what “affordable” means before. From a developer’s perspective, A2D has to make the numbers add up. It has to pay Camden a reported £25 million for the site, build 50% affordable housing that is less profitable, and still make a normal development profit.

Overall, 79 of the 164 units are designated “affordable”: 44 social rented (at a to-be-confirmed 40% of market rent) and 35 shared ownership. Whether shared ownership truly constitutes affordable housing is another debate.

Different types of ownership proposed for 156 West End Lane. Source: Design and Access Statement

What does it mean for West End Lane?

Sometimes, a focus on design and other issues can be at the expense of practicalities, for example the Sager building (Alfred Court) by Fortune Green was approved with an internal courtyard for commercial deliveries— but the entrance is too low for delivery trucks to enter. Yes really!

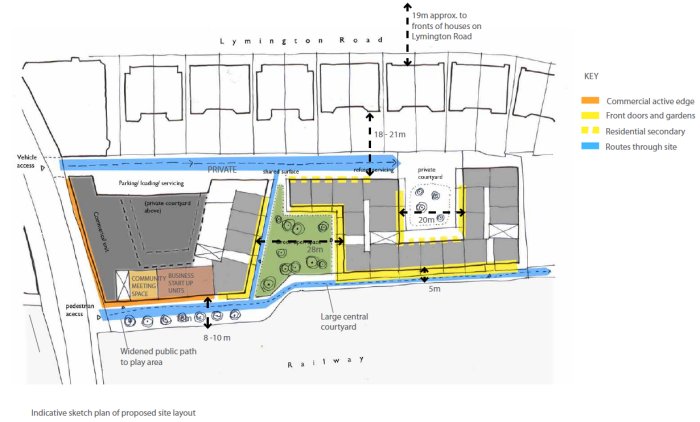

Deliveries could be an issue for 156 West End Lane too. The original plans claimed that the proposal met Department of Transport delivery criteria and would allow refuse collection and ‘small’ articulated lorries to back into the internal loading bay, but it seems tight. If, as with Alfred Court, it turns out to be impossible, then lorries would park on West End Lane and we’d have an escalation of the problems caused by Tesco lorries and more traffic chaos on West End Lane. No thank you.

As we discovered with Tesco, once deliveries start, it is nigh impossible to change them, so it is really important that this addressed at the planning approval stage and not left to be finalised later. There is also the practicalities of vehicles crossing the pavement onto West End Lane.

A serious issue hanging over 156 West End Lane is the size of the retail units. The focus on TP and employment space has led to less scrutiny of what the new commercial space will actually be. One reason the current building is so unpopular is that it is ‘dead’ frontage on West End Lane. To be successful it needs to be ‘active’ frontage, but another large unit on the scale of Wickes would not be much better.

Dull frontage on West End Lane – new development can, and must – do better than this.

Of course, planning has little control over this; it can specify only that the space should be retail, it cannot dictate the size of the units. The latest plans propose a flexible retail space potentially up to 678m2. That’s supermarket size. Yet would replacing the current frontage, which is rather dull compared to the variety on the rest of West End Lane, with another uniform frontage be any improvement? Even the option of three retail units would still see three sizeable units, but this is perhaps the least worse option.

A2D has promised that as site owners, it will be a good neighbour. Yet it is probably in its financial interest to lease the retail space as one site. With three —soon to be four—supermarkets on West End Lane, does West Hampstead really need another one?

What is the impact on local amenity?

What even is “amenity”? In this case it’s both the useful facilities of a building and the impact on the “pleasantness” of an area. The proposed development will affect amenity in both good and bad ways.

Firstly, your personal taste will dictate whether you think the building itself will enhance the area. Few would argue that it is replacing an unloved building. But as we’ve seen, the impact on views and sunlight is more contentious.

The development will create a new public open space and improve the rundown Potteries path, both positive impacts. A2D is also building a new community room, though it is not clear who will bear the cost of managing it.

Finally, A2D will be required to pay CIL (the community infrastructure levy that replaces the old Section 106 money) although it is not clear exactly how much it will have to pay but the most likely scenario is that it will have to pay £250 per m2 on the 7,657m2 of market housing, which comes to £1.9 million (25% of which stays in the area) plus £25 per m2 of the commercial space. This would allow improvements to other local facilities though tracking how this money is spent is a whole other issue.

Conclusion

The plans for 156 West End Lane show, yet again, that the planning system doesn’t work effectively. London is desperately short of housing and this scheme provides both private and social housing. It is being put forward by a housing association (which is using private development profits to build more social housing). And all that seems to have got lost.

No wonder; go to Camden’s planning portal and there are now more than 400 relevant documents online for this one plan. It’s overwhelming and nigh on impossible to get a handle on them all. This is not to say that the proposals are bad, just that it’s extremely difficult to judge them in an objective way. In fact, the latest plans are an improvement on the original versions – the design is better and they are quite a bit lower. A cynic might wonder whether A2D chose to start off with the worst-case scenario and then be seen to reflect local feedback to end up with what it had in mind all along.

The situation is complicated further by the fact that the fate of this Camden-owned site will be judged by… Camden councillors. Camden’s planners do seem to have influence on the proposal – their reservations (along with those of the GLA), were why the scheme was put on ice last year. Nevertheless, there is an annoying – if understandable – lack of transparency on their discussions so we don’t know exactly what issues concerned them. Once the planning officer reaches his decision – which will be a recommendation to approve or not approve, the decision goes to a vote. Given Labour’s dominance in Camden, and this redevelopment helping fund the new council offices at Kings Cross, there seems little doubt that if the recommendation is to approve, the same verdict will follow.

There is one significant issue that could derail it. The issue of employment space that we set out above is being challenged by deep-pocketed Travis Perkins. It’s a technical planning issue, and not top of the list of local concerns, but it could still have an influence as a legal technicality.

West Hampstead is having to cope with a lot of new development, and 156 will add to that; but are we getting our fair share of the benefits? Camden’s other growth areas – which it needs to meet its housing targets – have had money spent on masterplanning, but West Hampstead has not. This means that there are a series of disjointed developments that lack coherence.