Poison in the Blood: Three cautionary tales

The three stories here show how rural the area was in the 19th Century and how early medicine attempted to deal with rabies.

Be careful where you sit!

The following report appeared in the newspapers in late June 1858. Mrs Hoxwell who lived in Park Street near Regent’s Park, was “Walking in the fields in company with some friends at West-end Hampstead, when sitting down upon the grass,  A female adder with the distinctive zigzag pattern[/caption]

A female adder with the distinctive zigzag pattern[/caption]

The snake, more commonly known as an adder, was killed. Mrs Hoxwell received “The usual remedies” at a nearby doctor’s house before being taken home. Despite gloomy comments that she was “Not expected to survive”, no one named ‘Hoxwell’ died in the weeks following the incident, so reports of her death may have been exaggerated. Although the bite of a European adder can be very painful, it is rarely fatal.

Nine persons poisoned at Kilburn

In the late afternoon of Sunday 22 September 1889, nine Kilburn residents, including a three year old girl, were rushed to St Mary’s Hospital Paddington. One report described them as “Half-blind and in a violent delirium.”

What could have caused their dreadful condition?

That morning, a number of friends had gone for a walk, following the line of the Midland Railway (today’s Thameslink) north towards Cricklewood. They included three neighbours from Palmerston Road: 30 year old Henry Lansdown; William Pye, a 27 year old house painter and 23 year old carpenter Henry Holman. Spotting a bush covered in wild berries, they tried them and found they tasted very sweet. Lansdown and Holman picked a large quantity to take home. But unfortunately, they didn’t realise they were harvesting Belladonna berries, commonly known as ‘Deadly Nightshade’ and extremely poisonous. Their wives made fruit pies and the families enjoyed an unexpected treat for dinner. Then one by one

they fell ill, but after several days in a critical condition, luckily everyone survived. William who had eaten most berries was violently sick, which probably saved his life.

Surprisingly, given the potential for a further and possibly fatal accident, no one removed the plant. A year later the story was recalled by a local doctor who commented: “A single shrub of Deadly Nightshade, of exceptional size, grows by the side of the Midland Railway a quarter of a mile north of Mill Lane”. He concluded the seeds must have been “transported” to Hampstead by the railway, as the nearest plants grew some distance away. (Oxford Ragwort was spread round the country in a similar manner).

Mad dogs and English men

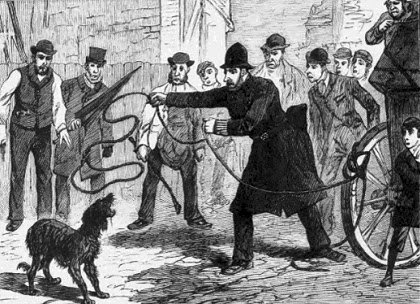

Death from the bite of a dog suffering from rabies was a regular occurrence in Victorian England. The only ‘cure’ was to cauterise the bite with a red hot poker. Aside from being an extremely painful and disfiguring process, it wasn’t always successful. Some victims were sent to Paris for treatment by Louis Pasteur, who in July 1885 had developed a vaccine to treat rabies, his motto being “Last bitten, first served”! The statistics show how successful Pasteur was: in the first four years he vaccinated 6,950 people, of whom only 71 died.

During a rabies outbreak, dogs were legally required to be muzzled. When this happened in 1896, the London County Council issued a muzzling order on Monday 17 February; unfortunately the day after two Kilburn men had what one reporter called, “an exciting encounter” with a mad dog. A nursemaid and two children were walking along Salusbury Road accompanied by the family dog, when it was suddenly and viciously attacked by an unmuzzled fox terrier. The animal was rabid and foaming at the mouth. The girl tried to beat the terrier off, but it snapped at both her and the children. Fortunately Harry Avriall (an advertising bill poster) and P.C. Monaghan came to her rescue. They chased the dog into an empty house where they killed it, but not before it had bitten both men on their hands.

The Kilburn Times noted that policemen were regularly carrying lassoes to catch dogs without handling them. The two men had their wounds cauterised as soon as possible. It was agreed the police would pay for their officer to be sent to the Pasteur Institute for treatment, but it was only a last minute donation from an anonymous benefactor that allowed Harry to go there. On arrival in Paris, the police constable’s wounds were found to be clean but Harry’s bite was inflamed and had to be cleaned using acid. Then both men were given the vaccine. Pasteur believed you needed to ‘work’ rabies out of the system so as part of the cure, they walked at least five miles every day of their two week stay. After the second injection which caused some stiffness, first Monaghan and then Avriall returned to London. Again, so far as we know, both recovered: Harry was living in Harrow in 1911 and still bill posting.

On 17 April 1896, the Times reported that since the muzzling order had been made in London that February, 13,608 dogs had been seized. Of these, 42 were rabid and had been destroyed. Despite the awful consequences of being bitten, the practice of muzzling divided opinion among dog lovers. The so-called ‘muzzle maniacs’ who wanted nationwide muzzling for twelve months to ensure the complete eradication of rabies, were up against the anti-muzzlers, who refused to believe that dogs could go mad. The Marquis de Leuville, whose biography we’ve written, was prosecuted for not muzzling his dog. He wrote a comic song called “Muzzling”, where the cover of the sheet music shows a terrier with appealing eyes, looking out from behind a large muzzle. “Written on behalf of many faithful suffering dogs,” the lyrics reveal de Leuville’s ardent belief that muzzling was cruel, while one advert directly appealed to like-minded pet owners: “Everyone who has a dog should get the song now.”

Local shop owner John Symonds, a harness maker at 37 Kilburn High Road, understood the power of advertising. He made muzzles and used his own dog as a canine billboard. It became a common sight in Kilburn to see his dog walking the streets, wearing a muzzle and with a cloth on its back, giving full details of Symonds’ store. For several weeks a local photographer displayed a photo of the dog in his shop window; muzzled, wearing specs and appearing to read a newspaper.

Rabies continued to menace the population with sporadic outbreaks up to the 1920s, largely attributable to imported dogs. Locally, in February 1900, Mrs Lilian Lancaster was bitten by a mad dog while visiting friends at Cricklewood. Her wound was duly cauterised at a local chemist shop, and the census shows her living with her family at 14 Weech Road a year later.

In June 1900 a Scottish terrier foaming at the mouth was secured by the police in Winchester Avenue, off Willesden Lane. Its owner reluctantly agreed her pet could be shot by a resident, who owned a revolver. British Pathe Newsreels has a silent film clip dating from about 1914, of a muzzled dog, entitled, “Who said “Rabies”? Fido strongly disapproves of the muzzling order!“

Comments

Poison in the Blood: Three cautionary tales — No Comments

HTML tags allowed in your comment: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>